On our first full day in Ukraine, our team leader, Greg, took us to visit an old friend. This was the day that we marveled at how we seemed to be living out the movie Everything’s Illuminated. There were the endless fields and meadows of Ukraine, the waving crops of sunflowers, the back roads that went on and on, the crews of shirtless men hard at work, and the “very rigid search” (to quote the movie) ending at the home of an elderly lady. But our “rigid search” was even more so than in the film, everything larger than life, deeper, and more wondrous.

Julie and me in the village of Bushcha, western Ukraine, June 2013

Village of Bushcha

First, some of the roads we traversed were so rough that they made even Pittsburgh look like civilization. “How does this van survive?” I asked Greg, shuddering to think of making the drive in my own little old Honda. “It’s built for it,” Greg answered. I believe we saw in person the grandest pothole in creation — one place in the dirt track where it seemed the most famous and accomplished potholes from every continent had sought each other out and founded a colony in mockery of man’s paving-over of nature. We eased past this place, treading softly, as the wheat whispered around us.

Cobbled road entering the village of Buderazh

Many rural stretches of western Ukraine are crossed by cobblestone roads laid by the Poles. For modern vehicles, these are rough as cobs. So what people do, when the ground is dry, is drive beside them, which forms a bare dirt track. We were there at the height of summer, so we could follow these parallel smooth routes, making the going much easier. When there was no such dirt track, sometimes there was a footpath beside the cobbled road, and Greg would put two wheels of the van onto it, cutting the jarring by half. He would steer back onto the road, of course, when we needed to give way to a babushka grandmother, a motorcycle with a sidecar, a bicycle, or a horse. (Sometimes I had to look long and hard to see if the random horse had an owner; it wasn’t always obvious, the horse’s people strolling along a quarter-mile away.)

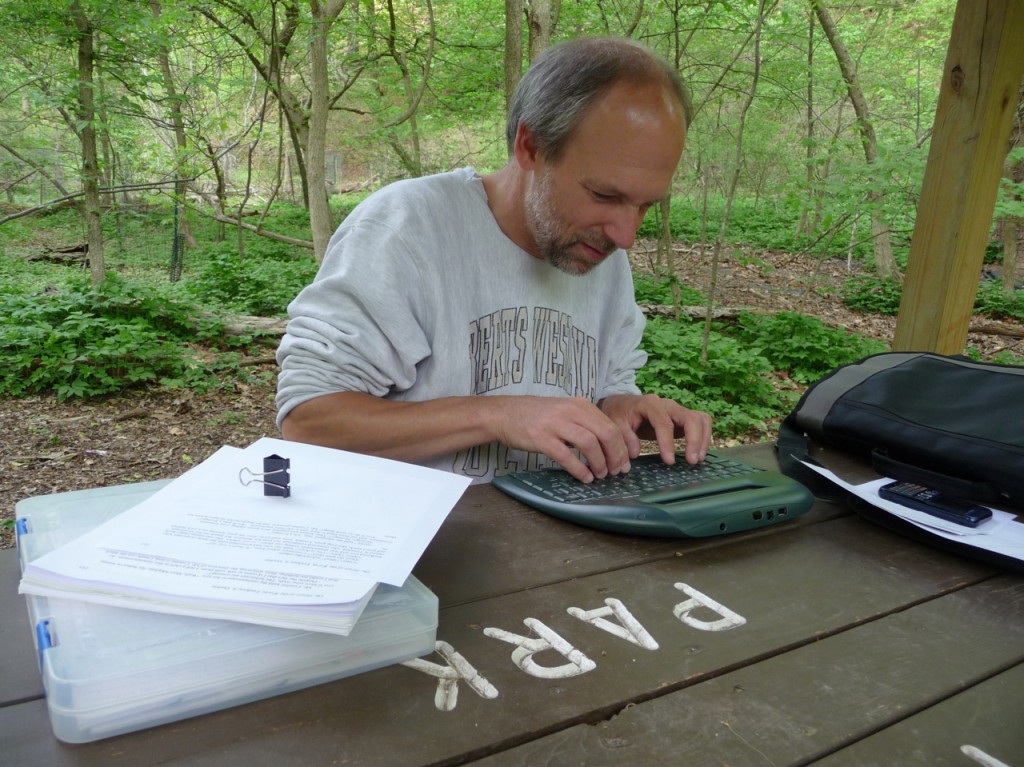

Me with a bottle of kvas in a cornfield

So we left the city and passed deep into the countryside, through wheat and sunflowers, to the very end of a Polish road. And there we came to the cottage of Katerina. Greg first met her years ago when he was out exploring. They became fast friends, and ever since, Greg has made a point of visiting her whenever he’s in the area.

Visiting with Katerina

Now, you must understand, there’s no way to call ahead when you visit Katerina. You can’t e-mail her. It’s the same as the shut-in visits I experienced among the Cree in northern Ontario. You just go across the wilderness to the house and wonder if the person you’re going to see is still among us on the Earth. We had some doubts as we parked at Katerina’s. The path seemed overgrown in the fullness of summer. There was a deep stillness over her orchard grove in the midday heat.

Behind Katerina’s house

But sure enough, as we pulled the van up beside her gate, the door of her summer kitchen swung open. Katerina, who is all but blind, came carefully up her path to see what the winds had blown in her direction. She was wizened and slight, her hair tied in a scarf. When she heard Greg’s cheerful greetings, she flung her arms around him — and around all of us, one by one, and planted kisses on our faces. It was remarkable to come so unannounced, and yet to be greeted so warmly. This, I thought, is village life, where human contact means a lot; where people, as a counterpoint to their hard physical work, truly value the words and the presence of others.

After the initial introductions, Greg asked Katerina to show us her garden. She waved a hand in self-deprecation, but was persuaded to lead us through a gate and into the verdant cavern of her yard. Trees formed a green ceiling above. Katerina lives in the humble summer kitchen behind the cottage; if I understood correctly, she doesn’t want to live in the cottage itself, where her sister passed away. A little dog yapped in defense of the property; Katerina spoke to it, and gradually it warmed to us, sidling toward our outstretched hands. She showed us her rows of vegetables and invited us to pick handfuls of strawberries. Beyond a haystack, the green fields tumbled away. We were met there by her nephew, a middle-aged man in an open-collared shirt and ball cap, who hung back behind the group and gladly spoke with Julie in Ukrainian, asking questions and telling us about himself.

Svyeta, Katerina, and Greg

We moved back out to the front, where Sasha, a member of our team, trimmed some branches away from the gate at Katerina’s request. She had a bench tucked among leaves and flowers. Katerina sat there, with Greg and Svyeta on either side, and the rest of us sat on the grass in a semicircle. We prayed together, Svyeta read some Scripture passages, and we sang praise songs. Julie had written out the words to a couple of these in English letters so that I could sing along. Katerina was perplexed that I could sing Ukrainian but not speak with her. All the while we read, spoke, prayed, and sang, her nephew leaned on the gate and listened, sometimes chiming in with a comment. Greg later told us of how every time he visits Katerina, someone else also comes along and gets involved — a neighbor, a passerby . . . Before the visit was over, we all got abundantly kissed again, and Katerina hurried off to her kitchen and returned with her apron full of pumpkin seeds. These she poured into our hands and a sack for us to take along.

For one week, we stayed in the village of Bushcha. Our host family was a woman, Olya, and her fourteen-year-old son, Vitya (a nickname for Victor). Olya’s husband, serving in the military, had drowned when Vitya was very small. Olya spoke freely with Julie, who helped her weed the extensive garden and chatted with her in the mornings and evenings. One evening, Olya told us more or less her life story. Julie was impressed by how, despite the difficult life and hardships Olya has had, her attitude is one of thankfulness to God; she emphasized how the Lord has taken care of her and Vitya.

Dave and me, washing dishes in Olya’s kitchen; Olya had the exact same fly strips dangling over the table that my mom used!

How to describe village life? Olya’s house was simple but not tiny — about six or seven rooms that I was aware of. It had a bath/shower room with a washing machine, but no indoor toilet. There was an outhouse built to share a rear wall with the barn. Instead of a hole beneath the outhouse, a square opening in its floor served as a socket for a plastic bucket. When this became full (which it did quite rapidly with the onslaught of our team of nine), Vitya or Olya would empty it in a location we never learned.

We tried to avoid drinking tea or coffee before bed, so that we wouldn’t have to venture out in the night; but we almost always had to. There’s something about not having a toilet indoors that makes you acutely aware of your bladder, especially when you’re bunking directly on a wooden floor. To get to the outhouse, I would grope for the little flashlight that Sasha made available; trying not to disturb Sasha and Misha, I’d slide open the partition to Svyeta and Tanya’s room, tiptoe through a corner of it, and tug open the noisy, unwilling door into Greg and Dave’s colder, outer antechamber, where they slept on cots. I’d ease past them, push through a curtain, and pull open another door. Then I’d cross the vestibule, find a pair of outdoor slippers to put on, and enter the yard. A couple nights, it was raining hard. When I circled to the back of the house, the dog would snap to alarm and bark. The cow would moo at me. Inside the outhouse, spiders would skitter out of my way and huff at me for breaking strands of their webs. Mosquitoes would begin feasting on me. I confess that I would usually hold the flashlight in my mouth to free up my hands. It was an awkward business. But always, coming back from the outhouse, I would stand in the yard beside the cow pen and marvel. I would gaze into the rain, or up at the stars, and into the woods, and revel in the stillness and peace of the place.

There were chickens and downy yellow baby chicks, too, and a rooster that would crow at dawn and then whenever else he felt like it, as a bonus. There was a root cellar where Olya keeps things like potatoes and bottles of kvas, a drink I really liked made with bread, molasses, and sometimes things like grape leaves; it just begins to ferment, but not quite to the point at which it becomes alcohol.

Sasha, Dave, and me drinking kvas sold by a sidewalk vendor in Rivne

The villages in western Ukraine are typically laid out in a long, straight line along a main road. People’s fields may be off in the distance somewhere, but the houses are generally close together, side-by-side. If you walk along the road from end to end, you will pass everyone’s front gate. Motor vehicles attract attention, and if you drive into town in a van, everyone will notice.

Load of hay in Bushcha

All up and down the road, horses pull wagons loaded with lumber, rocks, or hay. Some horses are hobbled to graze in grassy verges. Families of ducks cross the track — mothers and their ducklings. Goats munch on weeds and whatever else they can find. Tiny children with leafy switches herd obliging cows. The sun blazes down on soft, shimmering willows. Wooded slopes rise to one side, and a lazy creek wanders among trees beyond a meadow to the other. Spaces are immense. People drive cars down the cattle tracks to hold picnics beside the creeks, blankets spread out, radios playing pop music. People swim. Log bridges span the streams.

Yes, we drove the van down this road to the river.

At the edge of every village, a tall cross stands, brightly decorated with streamers of cloth and other ornaments — perhaps these represent the village in some way. I saw objects such as hammers, tongs, and the outlines of anvils dangling from the crosses.

In Bushcha, our team held a Bible camp — like a vacation Bible school. An average of about fifteen children came on the five days of the camp, plus a few parents. A very significant aspect of this program was that it was planned and led by the Ukrainian team; we from the States were there to help and support. Misha made initial contacts and found us the venue and arranged housing; Svyeta presented lessons from the Bible; and Tanya planned and led the activities. These team members were joined by Julie with her guitar and song-leading, by Sasha with his youth-camp and Bible skit experience, and by Kayleigh with her expertise in ministry among children.

Bible camp, village of Bushcha

A girl at Bible camp

Crafts at Bible camp, Bushcha, June 2013

Greg, Misha, Dave, and I served primarily in the nearby village of Borshivka. There, Misha had established contact with a lady named Luba who needed some home repairs. The chimney of her cottage was essentially a stack of loose bricks; the roof was of rusted sheet metal through which the sun shone.

Luba’s house in Borshivka; me and my wood pile; Misha and Luba explaining the task

Luba’s roof, insulated with rope woven through the rafters

On our first day there, Dave and Greg reinforced and mortared the chimney while Misha made the long trip back to the city for additional roofing supplies. I spent that day chopping wood to fit into Luba’s stove. Luba brought me two axes out of her shed and showed me the chopping block, a stout section of tree stump that I could roll down the hill to the new wood pile. Misha, Greg, and Dave each taught me a trick or two about woodcutting, and I was all set.

Splitting wood at Luba’s

Luba’s younger child is a boy, Svyatislav, who has just finished second grade. His third-grade cousin, a girl named Mari, lives nearby. These two were my audience/cheering section. They watched for hours — literally — sitting on the fence nearby (with breaks to chase each other through the yard), Mari clapping and shouting “Wow!” as I split each log and teaching me English phrases she’d learned. Svyatislav — or “Slav,” as Mari called him — was mostly the silent observer, very observant and thoughtful. He devised a way to help me by tying a cord around several large lengths of wood and dragging them over to me for chopping. He repeated this task again and again. When we guys were all working on the roof, he climbed up onto the top fence rail so he could be in a high place, too. He reminded me a lot of myself at his age.

Wood-chopping, with cheerleaders; Luba in the center

Once, two men in a horse-drawn wagon clattered to a stop in front of the house. The driver was dark-complected, with the often-seen Ukrainian combination of mustache and no beard. His companion was blond and clean-shaven. Both glared at me and scowled, which is simply how the culture works. People don’t grin and wave at strangers. But even knowing that, I was convinced these men were angry at us for being there. I respectfully stopped chopping and stood at awkward attention. (Many times on this trip I found myself on the verge of blurting out Japanese or trying to hear Japanese in the conversations. But Japanese language just doesn’t work in Ukraine . . .)

Only the driver spoke. He asked me questions and was confused by the fact that I couldn’t answer. Mari was off somewhere, but Slav explained to the men that not all of us could talk. The driver frowned at that. At about this point, Misha realized we had company and hollered down from the roof. The man hollered back. Neither sounded at all happy, but the exchange ended with Misha saying “Dobre,” which is “Good,” and the wagon rattled away.

Later I asked Greg what all that had been about. He said the men weren’t angry; they had come to ask how they could get in line for whatever service we were offering, because they also had a roof that needed fixing!

Mari and Svyatislav

I remember in particular the bright colors of those days. The villages are an intense backdrop of green — soft crowns of trees that look like they’ve been painted with a fan brush . . . rolling hills of grass. Cottages come in every color. There’s the brown of horses and cows passing by, the yellow-green of hay piled high in wagons or stacked in fields. Chickens are splashes of white. Mari and Slav were fair-haired like little Norse children, but small and slight, and really active.

This was a time when I most felt the hand of God at work. Dave and I didn’t speak the children’s language, but it really didn’t matter. They watched us. and Mari never ran short on things to tell us or to teach Slav, pausing her cheerful chatter only to draw a breath. Once when Misha and Luba were talking nearby, we chuckled about how I had quickly picked up the art of log-splitting, and Luba said that you learn about life from chopping wood.

Dave caulking holes in the roof at Luba’s house in Borshivka

That roof was quite an operation, too. Dave clambered up into the attic to caulk the holes. (There was one interior ladder for people and a second, smaller one for the chickens, which also, for reasons we never quite fathomed, needed to go up into the attic now and then.)

The ladder for the exclusive use of the chickens

We all took turns on the outside, painting the surface with a sealant. As the week drew to its close, we were racing the calendar a bit, striving to finish what we’d started.

Me and Misha, painting the roof

Lunch at the job site; Dave and me

One challenge was the stinging nettles growing thickly against one side of the house. Dave and I got into these on the first day while setting the ladder in place. Another was the steep pitch of the roof, and the third was the ladders themselves. These were not aluminum extension ladders from a hardware store. These were wooden and rickety, one with rungs so delicate that we placed our feet with great care against the upright sides, fearing to put any weight toward the center of the rungs. But everything held. On each side of the cottage, we had one ladder leaning against the eaves and a second lying flat on the roof to support us once we were up there. (We didn’t dare to step or lean on any part of the roof itself.) These upper ladders had top ends made to hook over the peak of the roof. The extra wood required for this right angle made the ladders extremely difficult to manipulate from below. We did our best not to trample the vegetables in Luba’s garden. When we needed a longer ladder for the end of the house where the ground was lower, a neighbor lady, also named Luba, lent us hers. We hiked up the road to fetch it, and then Greg, Misha, the ladder’s owner, and I all worked with saws, hammers, nails, screws, and an electric drill to rebuild and reinforce it. A neighbor girl came over with her puppy. It was quite a merry gathering.

A precarious perch

Building the new ladder; the second Luba at left; puppy; the mission van

The scariest part of the whole adventure was a bare electrical wire that ran across half the roof near the lower end. To paint that part, we had to work and crawl directly under this wire. Dave knew enough about wiring to recognize it as something that would deliver a possibly fatal jolt if touched. So for that section, we kept one man on the ground at all times whose sole task was to watch the guy on the roof; if the painter got close to the wire, the one below would warn him. Even when you’re trying to remember the wire just above your back, it’s all too easy to get engrossed in the job and rise up without thinking. So I think Dave and I saved each other’s life at least once. We would call out distances — we felt like deck hands on the old riverboats paying out the knotted ropes and hollering “Mark twain!” In our case, it was: “You’re about two feet from it . . . foot-and-a-half . . . easy . . . keep your bottom down . . . okay, you’re out of the danger zone.” When the painting was all done and we were far away from Luba’s roof, Dave and I enjoyed standing on our tiptoes, stretching, and flailing our arms in the air, just because we could.

A very nice gesture came from some ladies at a church back in the States. They hand-made dresses for young girls and sent these along with Kayleigh. One day, Kayleigh came out to Borshivka and gave dresses to the girls there, explaining where the dresses came from, that they were made for the girls with love, and that God loved them, too — that they were each His unique creations, His children, and very special. The girls were completely delighted and ran indoors immediately to change into their new attire.

A girl and her mother receive a dress from Kayleigh.

Ah, Ukraine! (I think this was in front of Katerina’s.)

One aspect of what we did was helping a family who needed some work done. Others of us conducted a camp. But even more importantly, our team came with kindness, diligence, sobriety, and patience into the communities; we came in the name of Christ. If our actions and attitudes served as reminders for anyone of God’s love for us all, it was worthwhile. If people like Mari and Slav, when they think of Jesus, church, or the Bible, will link those concepts to the gentle, positive people who visited them, maybe it will help them to see that faith is alive, that God’s love is real.

The Ukrainian team also brought along Christian movies that were shown in the village “club” — a community center — on two evenings.

There are still more things to write about, but I’m going to stop there for now. I have to tell you about castles, ghosts, a man of peace, a well, and an underground monastery. You won’t want to miss it. See you soon in Part 4!