Such busy, busy days and nights, and so much happening! It’s been one of the best Octobers I can remember in quite awhile. For the most part, the weather has been gloriously warm and sunny, and I’ve spent as much time outdoors as possible. (The sun is so rare in Niigata that when it comes out, you drop everything and run outside in full absorption mode.)

Seriously, where to begin? First, the Fan Art is beginning to roll on Cricket‘s website, and they’ve got the first three pictures up of “The Star Shard” done by young readers. (www.cricketmagkids.com) I can’t describe the feeling of seeing artwork drawn for a story that entered the world through my mind and fingers. It’s humbling . . . it’s moving . . . it’s awesome . . . it’s — well, indescribable! Actually, it’s the second time I’ve had this rare joy. The first was years ago, when a teacher friend cajoled his students into drawing various villains from Dragonfly. I still treasure those. When kids draw the Harvest Moon heavies, they’re terrifying!

Second, just today, a friend passed along to me a review of Dragonfly written by a friend of hers on LiveJournal. (Ooh, am I allowed to say that on WordPress?) It’s truly uplifting to know that someone somewhere curled up with my old book and spent the day riveted. That’s the wonder of art. That poor book has been wandering around out in the world for close to a decade now — knocked around, remaindered, pulped, offered for sale on Amazon for a penny. . . . But it still connects with readers now and then. It still offers a world to escape into. This reviewer gave it an “A+.” She writes:

“Today was a good day. I spent it in bed under my pink polka-dot blanket reading page after page of Dragonfly until I could read no more and it was finished. /…/ I found it utterly fantastic. /…/ Frederic S. Durbin creates an entire world in only 350 pages [sounds like the paperback], and I would have to say that the world he creates is one of the biggest, most creative worlds I have ever ventured to by way of reading. /…/ Throughout the end chapters of this book I found my eyes welling with tears. I honestly did not know how this book would end up until the very last battle, and even then I had my doubts; but I will leave you to find out which side prevails.

“I think that everyone that enjoys embracing the dark side of life or ever wonders what hides in the shadows of a dark room will enjoy this book because it acknowledges our worst fears. I also think that anyone that enjoys female leads will find entertainment in this novel. Dragonfly is a strong and witty little girl wise beyond her years.”

Soli Deo gloria! And thank you, o thou friend-of-a-friend!

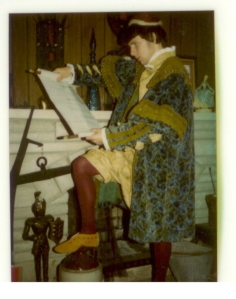

So, I’m about to head to Calgary for this year’s World Fantasy Convention. I’m really excited about that, as you can imagine! I’m scheduled to do a 30-minute reading again this year. Last time, I opted for three shorter selections to fill the half-hour, going for variety. This time, for the sake of experimentation, I’m planning to use the whole time to deliver one unified whole — namely, the Brigit and Phocion section from “Seawall,” the last novelette in Agondria. I chose that one because it’s an encapsulated, standalone tale, and because I think it’s some of the best writing in that book. (It gives me a little chance to act, too! Oh, the drama! “Alas, poor Yorick!”)

At the Convention, I’m also planning to have lunch with my agent on Friday. It will actually be our first face-to-face meeting. He is truly worth his weight in gold and then some — he’s working so hard to get my novel-length version of “The Star Shard” sold to the best possible publishing house. (I’m now thinking of calling that novel The Star Shard. Isn’t that brilliant and innovative? Maybe some fans of the story will notice a connection between the titles!)

While I’m dropping phrases like “my agent” and sounding all like a hoity-toity writer, I’ve got to tell you about a day I spent recently. The theme of this posting is a writer’s life in October, and this day in question, my major activities really sound like I’m living the writing life — like a page from the G.Q. of Writers, if such a magazine existed. Heh, heh — read on:

First (this is all one day, mind you), I made notes on a bundle of my poems from my old chapbook Songs of Summerdark at the request of a colleague at the university. She’s a composer who delights in setting words to music, and she wants to take a whack at some of my poems. So I was going through picking out poems, suggesting instrumentation, and writing notes on what I was trying to capture in the poems and what I thought the instruments and voices should be doing. It will be great fun to see what she comes up with!

Second, I worked on timing my reading for the Convention. The only way to do that is to read it more-or-less aloud from beginning to end and notice how much time elapses. I ended up cutting a bit from the middle.

Third, I put together a promotional package of some things for The Star Shard to deliver to my agent when we meet. I try to keep him supplied with anything and everything that might be useful in selling the book.

Finally, I read and carefully critiqued a novelette for a good friend, which was pure joy, not work.

If that ain’t livin’ the writing life, I don’t know what is! I’m thankful for the chance to be here, to be now, to be doing the things I’m doing. It’s not a matter of course — it’s a matter of grace. I’m thankful for the sunlight this October. I’m thankful for my students . . . for words on paper . . . for imagination and the coming of Hallowe’en . . . for the gift of participation in this incredible, unforeseeable sprawl that is life.

Speaking of Hallowe’en: I’d like to encourage another round of reader participation. Are you all still out there? If so, we can’t let this holiday slip by without a proper celebration — a proper revel in smoky lantern light while shadows caper. Two questions I offer: you can (ideally) answer both — or one. (Answering neither is not an option!)

1. What do you do to celebrate Hallowe’en? If you love the season, what is one thing you do to make it particularly shivery and delightful? Dredge up your dearest All Hallows customs and confess them here! A certain mode of decoration? A way you greet the trick-or-treaters? A book or story you read in October? A traditional jack-o’-lantern face you carve? Anything at all . . . how do you greet the long shadow season?

2. What is your favorite Hallowe’en memory? This is your chance to go into detail on that time you. . . . Or when you made that. . . . Or when. . . . Childhood? The threshold between childhood and adulthood? Later still? What was a particularly memorable Hallowe’en for you?

Okay, I’ll get you started on the memories. One Hallowe’en I’ll never forget was 2005. That was the year my mom unexpectedly passed away on October 18. I flew back to the States to be with Dad and for the funeral and all. On the day of the funeral, the town was breathtakingly gorgeous — trees a miraculous palette of brilliant reds and golds. The procession of cars to the cemetery was the grandest Hallowe’en parade one could hope for — couldn’t have ordered a better day for Mom’s last ride through the town she loved. I saw a whole lot of friends and relatives that I don’t normally see — all very loving and friendly, all gazing into Eternity and aware of the brevity of life, all with an awareness of how much my mom had meant to them. A surreal time, when I’m normally teaching but wasn’t that year.

The town was decked out in Hallowe’en glory: fake tombstones like gray toadstools in yards; chokingly thick webs in trees, covering bushes; scarecrow figures, jack-o’-lanterns, ghoul dummies, witches, oddities, orange lights. . . .

I bought Hallowe’en candy, which yanked a crown off my tooth, and I had to go to the dentist. I bought pumpkins — big, orange pumpkins, so abundant and cheap in Illinois, so rare and expensive in Japan. I carved them, and my dad smiled. He said they looked like a couple, this one male, that one female. I took pictures of them.

I took the jack-o’-lanterns to my aunt’s house, because she has the best location ever for trick-or-treaters — no kidding. She’s right on the main street, in the safest neighborhood in town, where parents trust and everyone is home in well-lighted houses, and kids flock thicker than clouds in August. We set the jack-o’-lanterns on the porch and lit them. We set out my aunt’s Indian mannequins: a man and a woman (though the woman is really a man wearing a wig and a dress — a transvestite Indian). They have feathers and moccasins and fringe, and older kids love them, and middle-kids gaze at them in half-terror, and babies fear them and bawl, but still their moms carry them to the porch to receive their Hallowe’en treats. I am proud of how some kids whisper to each other about my jack-o’-lanterns — “Look at their pumpkins!”

My aunt lets me hand out the candy. We are both still somewhat numb in this world without my mom. My aunt makes popcorn, and we eat it in the brief intervals between visitors. The intervals are brief — we have something like 150 kids the first night and nearly 100 the next. We run out of candy and have to buy more for the second night. My aunt keeps a tally, making a mark on paper for every kid that comes to the door. We laugh in the quiet intervals and talk about how many of the girls seem to be dressed as hookers. There’s vampire hooker, witch hooker, and just plain hooker.

One of the most amazing things is how kids appear out of the night. They materialize from the darkness out by the street. Some cut straight across yards, through the drifts of dry leaves, crunch, crunch, crunch. But some — usually boys — RUN from the curb, a skeleton or a Scream-masked horror swooping toward our porch. Kids stand under the street lights, comparing loot, plotting their courses. Tall witch hats tip and bob as they speak. Many carry little sticks that glow in phosphorescent colors.

I comment on the kids’ costumes (though I avoid saying things like “Oh! A hooker!”). Isn’t it odd how most kids seem oddly disinterested in their costumes? One girl has a knife through her head, with blood trickling down her temples. I say, “Wow. You might want to have that looked at.”

I’m wearing a flannel shirt. For some reason, that sticks in my mind — that shirt, in that surreal October of grief and the Otherworld. Candy, candles, trick-or-treaters. Dragonfly hit the mass market that year; it’s in stores, in Barnes & Noble, in Waldenbooks — for a few brief months. I’m making it as a writer. I sit in a rocking chair opposite the door. I make the decisions about how much candy to put into each bag. My aunt sits off to the side, making her tally marks. She can see the kids through the plateglass window.

Toward the end of the evening, when the visitors trail off, and we’re eating the unpopped kernels that can break your teeth if you’re not careful, my aunt wants to call it quits. But I insist on staying open for business until the end of the time the city allows. I’m so low on candy that I can only put two or three pieces of boring stuff into each bag. But I want to stay as long as I can in my flannel shirt, up and down from my rocking chair, watching the dark, listening for the whisper and giggle of stragglers. A few bigger kids come, kids too old to be trick-or-treating — but, like me, clinging to this night.

This night. Hallowe’en. This year, this 2005, I’m halfway through writing “The Bone Man.” Mom passed away during the restaurant scene, and I got a phonecall in Japan from the coroner, because no one else in my family could make the international phone number work. “The Bone Man” will go on to receive honors — publication in Fantasy & Science Fiction [Dec. 2007], translation into Russian, anthologization in Year’s Best Horror, honorable mentions from Dozois as a science-fiction tale and from Datlow as a fantasy/horror story. It will be on the ballot for Locus and for the International Horror Guild in their last-ever round of awards. It’s on the ballot against a Steven Millhauser story. A couple people nominate it for a Nebula. Wonder and love and family, sadness, childhood, adulthood . . . Japan, the U.S. . . . life, death, loss, success, crisp air, the imagination. . . . Everything flows together. The world turns toward winter, but on these nights, we’re linked to the earliest times, the beginnings. We are all storytellers, said Paul Darcy Boles, sitting around the cave of the world. “Why don’t you write a Hallowe’en story?” a friend of mine in Japan suggested at the beginning of that October, when I was feeling down and agonizing over what to write. So I started to write “The Bone Man,” just to distract myself. Just to have fun.

Yeah . . . as wonderful as my childhood Hallowe’ens were, I think 2005 was my Hallowe’en, the one single one I’ll never forget.

* * * * * * * * *

Don’t be overwhelmed — mine was long, but short is great, too! What do you do to celebrate Hallowe’en? What are your Hallowe’en memories? Back me up here! Let’s hear from you! Come running from the dark. I’m waiting!