I find it gratifying and delightful that our oldest existing story native to English — the Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf — is unabashedly a monster story. Isn’t that wonderful? It’s generally dated to the eighth century, which means it has stood the test of time to reach us well over a thousand years later; we study it in our schools; our scholars analyze it anew in each generation; it has inspired novels, music, and films. And it’s a monster story.

It’s told well, of course. It’s a poem. It uses language that conjures pictures in our heads and brings music to our ears. It has characters we can relate to and it takes us fully into their world; in short, it does everything that good literature is supposed to do. And it’s a monster story! It satisfies the college profs, but it also satisfies the little kid in us who yearns for creatures that pad up to the door of the mead-hall and smash it asunder.

What does that tell us about fundamental, archetypal storytelling? All those of us who love a good creature tale can hold our heads high. Our kinds of stories were there at the beginning; they’re still there behind it all. Things go bump in the night, and all we who huddle around the fires want to hear about them — from a safe distance, if possible.

The title of this post comes, in part, from a phrase used in Beowulf to describe the monster Grendel. (In John Gardner’s 1971 novel Grendel, told from the monster’s viewpoint, Grendel describes himself as “a shadow-shooter, earth-rim-roamer, walker of the world’s weird wall.” Nice, huh?) The original epic Beowulf emerged at a time when Christianity was spreading among the pagan cultures of Europe, and the poem is a fascinating blend of Christian and pagan elements. [I remember reading another poem from the general era in which Christ was portrayed as a warrior-king, conquering death for His people in the same way that Anglo-Saxon kings conquered enemies. In the poem, Christ leaps up onto the cross, grips it in His brawny arms, and hangs on tight until He has strangled the last breath out of death, thus winning salvation for the thanes He protects. That’s a world different from the pale, suffering Christ depicted in later years, but they’re both aspects of the work He accomplished.]

In Beowulf, one manifestation of the Christian element is the poet’s painstaking effort to connect Grendel with the Biblical Old Testament. Grendel is descended from Cain, the first murderer. There is also some association with the fallen angels who warred against God and were cast out of Heaven.

Interestingly, there’s a correlation in our own times. Just as the early tellers of Beowulf felt a need to fit the monster into their Christian world-view, I’ve heard of a similar phenomenon going on today in Christian fiction publishing. (I’m talking about books published under the label of “Christian fiction,” not simply books by Christians such as The Hobbit.) A good friend of mine has spoken at length with editors and agents who work in this genre, and apparently the rule in place among many (most?) of them is that any supernatural element a writer uses has to be supportable with Scripture — in other words, if you use a monster, it has to be one from the Bible.

Where this comes into particular play is in vampire fiction. Believe it or not, my friend tells me that certain Christian publishers are actively seeking vampire fiction. It’s just that they require it to “have its theology right.” Really, it’s always been my theory that the older vampire stories in the western canon are inseparable from a Christian understanding. Vampires (traditionally) can’t endure crosses and crucifixes, right? They avoid churches. Why would this be, unless we’re acknowledging the power of God and God’s opposition to evil? (When people ask me what Dragonfly‘s category is, I say “dark fantasy, or maybe Christian horror.” Heh, heh!)

But, as my friend reports it, you can’t say a vampire is a “vampire” in official Christian fiction and leave it at that, because there are no vampires in the Bible. (Well, actually, there may just be a hint of them, but that’s a whole other posting! We can get into that if anyone’s curious.) So you have to say that vampires are demons masquerading as vampires. My response to that is, why can’t a vampire simply be a kind of demon? That’s the way it’s handled in Buffy: vampires are frequently referred to as “demons.” The soul of the human departs from the body at death, and the body is taken over by an evil, demonic spirit who is wholly other than the departed human, yet with an awareness and command of the residual mind and memories of that human. So it’s that human in a way, but without the most important part — the soul — and with something extra and evil added in — the demon. That, to the best of my observation, is the way it works in the Buffyverse, and that model works fine, theologically, for me! So there you have it: on this point, Buffy has its theology straight. (We won’t get into Willow’s religion. . . .)

But back to the creatures that walk in the night (not just vampires) — stories about them have sprung up all across cultures and throughout history. We humans can’t leave them alone. Theories abound as to why. Perhaps these tales grow out of our fear of the dark and the unknown; we give faces and physical forms to our fears, because any monster, no matter how terrible, is somehow easier to deal with than the truly faceless and unknown. Once we know it’s a dragon, we can work on how to defeat it.

Or maybe the stories are one way of dealing with the forces we know about but can’t control: storms . . . enemies . . . unexpected violence . . . illness . . . loss . . . death. Give it a face, let it pursue you for a while through a harrowing tale, and then overcome it. Escape.

Maybe the monsters somehow represent the mystery, power, and vastness of nature itself. This is a recurrent theme in the stories of Algernon Blackwood, particularly “The Wendigo” and “The Willows.” (Even my mom — my mom, who never went out of her way to read any horror — remembered “The Willows” as “the scariest story [she’d] ever read.”)

Or yet again, maybe our monsters are our way of separating out the bad parts of ourselves. The truth is, there’s darkness, greed, and malice inside us — monsters give us scapegoats. They siphon out this badness from inside us, and we can point our fingers at them and drive stakes through their hearts. That certainly may figure into stories of werewolves, which explore the notion that there can be beasts within us that sometimes emerge, terrible and separate from the part of us that is human. That all may be part of it. . . .

Or maybe we know that we really do live in a world where lonely things howl in the desolate places, and to tell their stories is as natural as telling our tales of journeys and discoveries, of courage and love and triumph.

Isn’t it interesting, though, how many of our monsters have been changing over the years? Vampires were once utterly evil, alien, and repulsive. Remember Nosferatu, with his pointed ears, his bald, bulbous head, his rat-like demeanor, prominent fangs, and the stark, twisted shadows he cast on the wall? Then came Bela Lugosi, who still portrayed an evil vampire, but was also charming and seductive. Ditto with Christopher Lee. Decades went by, and then came the Anne Rice vampire books, beginning with Interview with the Vampire, in which vampires were the main characters — we were inside their heads, sympathizing with them, understanding why they did what they did. We rooted for the good ones and hissed at the bad ones. When Joss Whedon gave us the TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer, we had vampires who — under certain conditions — could be noble and heroic.

And now we have an explosion of vampires in the pop culture, and in many instances the good-aligned vampires aren’t even sorry to be vampires — no one is sorry . . . they altruistically find ways to feed without harming humans, they help people, they’re beautiful and romantic, women and men swoon over them, and they’ve essentially become like Tolkien’s Elves: the species that we’d be if we were a little better — if our limitations and infirmities were taken away.

Mary Shelley undoubtedly helped to bring about this shift in the role of the monster. In her 1818 novel Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, the monster, though he behaves monstrously, is the victim; his creator is the true monster, the source of the harm and tragedy. So, too, in the latest retelling of Beowulf — the 2007 film written by Neil Gaiman and Roger Avary — the monster is both terrifying and greatly to be pitied; he is not so much ravenous as he is tormented. (And whoever thought back in the eighth century that Grendel’s mother would one day look like that — like Angelina Jolie covered in gold, wearing high-heeled feet?! Oh, the roles of monsters are a-changin’ . . . but perhaps not so much. There have always been sphinxes and lamias and succubi, so I guess even with gold, seductive Grendel’s mother, there’s no new thing under the sun. Or under the wan moon.)

Sooooo . . . something wicked this way comes, and if you’d prefer not to talk about it, then don’t. Turn back while you still can! But does anyone care to tell about the earth-rim walkers that particularly chilled and delighted you when you were small?

I’ll start us off with a few. First of all, my nextdoor neighbor Chris and I were convinced that there was a Bigfoot-like monster haunting the creek behind our field. (Or if we weren’t absolutely convinced, we worked hard to convince ourselves.) Since every monster needs a name that sounds both innocuously childlike and yet sinister and creepier the more you think about it, we called him “Funnyface.” We knew that he came up through the cornfield at night — we knew, because now and then we’d find a cornstalk that had been knocked down . . . by something obviously big and heavy. Any oddly-shaped depression in the field’s dirt became a partial footprint . . . any strange sound from the woods became his yowl. We found some scratch-marks high in a tree that we declared had been made by his claws. And the clincher — the final proof of his existence — came when we tied a piece of lettuce (was there some ham, too?) by a string from a tree limb — high enough from the ground, in our reasoning, that no small animal could get at it. And when we came back a day later, the lettuce was gone!

I won’t embarrass Chris with our other demons here, but I’d love to hear his recollections of them if he can be goaded into telling about them. (If not, I’ll understand!)

But also, a group of friends and I had a kind of club that gathered, during recess, under the apple trees at the far edge of the schoolyard. While other boys were playing “Kick That Ball” (that’s what they called it!), we sat under those trees and talked breathlessly in hushed voices about the monsters we had personally seen. And we saw them often! Talk about Sagan’s Demon-Haunted World! In our childhood, monsters were always popping out of hedges and shambling along roadsides, just barely visible in the twilight.

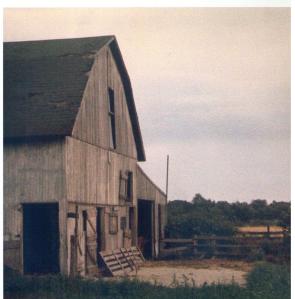

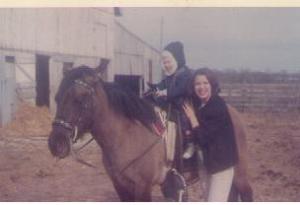

I told about Funnyface, of course. He didn’t just stay in the cornfield, either. Sometimes he lurked in the barn and watched Chris and me playing outside. Every now and then, we’d get an eerie feeling that we shouldn’t go into the barn. Those were the times when he was there, so we kept to the yard and peeked at the barn through weeds or over the edges of roofs.

I also had an Alien that poked his helmeted head above the multiflora rose bushes in the northwest corner of the yard — and always in the last gleam of twilight. He wore dark shades like sunglasses and had a long, hooked nose and protruding chin. I think his skin was blue.

And I had an Old Lady Ghost who is a separate topic unto herself — let’s save her for another time.

G. lived in a house where the yard backed against the railroad tracks. So his childhood was always full of the roars and rattles of passing trains, the mournful whistles in the night. His monster was a humanoid thing with long hair sprouting from its shoulders. G. always saw it only from the back (which we thought was just plain creepy!), and in the gathering dusk, the thing would jump up and down in place, away down the tracks. Up and down, up and down, in some bizarre monster ritual or dance, until it got too dark to see it anymore.

R. had a Deer Man — a furtive, tawny, human-like figure with big antlers on the top of its head. When R. looked out into his moonlit yard just before he went to bed, the Deer Man would climb over the fence, run lightly across the grass, looking around nervously, and then climb over the opposite fence and vanish into the night.

H. told of a giant frog named Old Smiley that inhabited the marshy creek behind his parents’ trailer court. H. would creep down there among the weeds and see Old Smiley sometimes, who was as big as a coffee table. Smiley would look at H. with his enormous round eyes, say “RIVET!” and hop into the water with a tremendous splash. What made this monster truly great was H.’s imitation of him. H. was a gangly kid, all bony elbows and knees, and his mom used to dump so much tonic on his hair that we called him “Syrup Head.” H. would show us how Old Smiley jumped: he’d crouch low against the playground and then uncoil himself, shouting “RIVET!”, and bound into the air. We laughed at how funny it looked. And then we’d look at one another and go “Ooo” in subdued voices, thinking about how it would be no laughing matter down in the weeds and the dark and the mud, with only a few lights from the trailer court off in the distance.

Finally, S. had a disembodied eyeball called Big Red who prowled in the bushes behind S.’s house. S. would part the bush-branches at times, gaze into the depths, and Big Red would be staring back at him.

Ah, Earth-Rim Walkers! Gotta love ’em!

Tell us your stories! Tell us, tell us!

It occurs to me that the passage of dark doorways is a primary element in the vast majority of these stories we hold so dear. Sometimes it’s a literal door, and literally dark. Sometimes it’s a figurative doorway, and the “darkness” is rather the mist of the unknown. Let’s consider a few examples, right after the following pertinent side note.

It occurs to me that the passage of dark doorways is a primary element in the vast majority of these stories we hold so dear. Sometimes it’s a literal door, and literally dark. Sometimes it’s a figurative doorway, and the “darkness” is rather the mist of the unknown. Let’s consider a few examples, right after the following pertinent side note.