We hear it all the time from writers, writing teachers, and the trade magazines: if you’re going to submit your stories or book manuscript for publication, learn to handle rejection. Develop a thick skin. Learn to discriminate among rejection letters, because there are bad ones, so-so ones, and very good ones. Glean what you can from them, and live to submit another day.

I thought it might be interesting to chronicle the journey of what I believe has been my most-rejected short story. This odyssey took place mostly in the time before everyone was using e-mail, and before most editors wanted anything to do with electronic submissions. So this story made its trips back and forth, back and forth across the Pacific in battered manila envelopes; it came back coffee-stained, just like in the stereotypes, to be printed out and sent forth anew. May this account of its rocky road to publication serve as encouragement to any who labor in the trenches, who plod onward because writing is what they do . . . and especially to those who wonder “Do I have what it takes? Will my writing ever see the light of day?” To all who love the arranging of words on paper — to all who would sell your words that others may read them and have an experience and see in their heads the pictures you see — I say: Persevere! Don’t give up. We continue to learn, and the road we’re on leads somewhere. The bottom line of my entire experience so far is this: Things happen when they’re supposed to, in the order they’re supposed to. Be the best you can be. Keep loving stories, keep loving people and life, and keep writing.

This is just about the season when, in high school, we would start marching band practice. In the sweltering heat of the middle of August, we would gather on the football field to learn the new half-time show. In that era, they were written for us — the music and the marching choreography — by a well-known professor / marching band leader from a university. As the football team grunted and crashed into each other in the distance, we band members would practice keeping our intervals measured as our lines swung and crisscrossed. With sweat stinging our eyes, we went through the bars of the Spanish Opener or Spirit of the Bull eighty times, ninety times, first just learning the movement on the field, then doing it with horns in our hands, then doing it as we played.

It’s quite a different thing to play on a marching field or in a parade than it is to play in the band room or in a concert hall. I suppose it’s something like the difference pilots feel between landing at an airport and landing on an aircraft carrier on the high sea. When you’re marching, your feet hit the ground, bam, bam, bam. The mouthpiece is going all over the place, mashing your lips, chipping your teeth. And none of that can affect your sound — if you’re playing a long, unbroken note, it has to be long and unbroken. If you’re a trombonist, you have to watch that you’re not whacking woodwind players in the back of the head with your slide. You have to keep your horn up parallel to the ground. You have to see the notes printed on that little flapping paper clipped just beyond your mouthpiece as you watch other moving people from the corners of your eyes — and oh, yeah, you’re supposed to watch the conductor, too. You’re burning up during the August practices, but you’re freezing during first-period band class on mornings in October and November, and at the late-season football games, your toes are nearing frostbite in those hard black shoes. You have to play loud enough so that the people in the stands hear more than drums. (I think that’s why there’s such a high burnout rate among marching-band clarinetists.)

Anyway, we had the best band teacher in the world, whose name was Jim Smith. That was really his name; it’s not an alias. In his marching band uniform, he looked exactly — exactly — like the band leader in the Funky Winkerbean comic strip (Harry Dingle?). Anyway — here comes the point of my story — we’d be slogging through this routine for about the third day, tired and irritated and wishing it were the beginning of summer instead of the end. And then Mr. Smith would order us to do the routine better each time. Don’t just mindlessly go through the motions the same way again and again. Every time you do it, he’d say, try to improve something. Concentrate. Or, as he would famously yell through his megaphone: “Find it! Find it!”

Mr. Smith’s patience and dedication, his excellence and attention to detail are still with me as I walk the writerly path. Don’t give up. Don’t go through wooden motions. Do it better each time. If a section is rough, take it home and practice it. If a section in your story is rough, spend the time — work the problem out. Write what you mean. Be conscious of what you’re putting on the page. Find it!

I also have to say this about Mr. Smith: he was one of a very few of my teachers who came to my local book-signing when Dragonfly was first released. He is a prime example of how the very best teachers teach much more than the particular discipline of their profession. They teach with their whole lives.

ANYWAY (I may have to pay the Pun Fund there for a very long, tangential story, but Mr. Smith is more than worth it. . . .) — here’s the journey of my most-rejected short story, “Under the Tower of Valk.” I’ll keep the editors anonymous so that I can quote from them.

1. First Submission: January 21, 2000

No response. On May 19, 2000, I sent a follow-up query.

No response. I waited until June 27, 2000 — well beyond the magazine’s posted response time, and then sent a last-resort follow-up by e-mail (a radical step with that magazine in those days — the editors were still pretty touchy about having their e-space invaded).

June 30, 2000: E-mail response from the editor: “O Frederic: No record at this end of either your manuscript or your follow-up inquiry. To save further time, and to avoid the risk of putting still more paper into the placid waters of the Pacific, I suggest the following: convert your story into a pure text file. Mark the beginning of any italics/underlining with ** and the end of any italics/underlining with * Indent each paragraph five spaces; and Just In Case, put a blank line after each paragraph. Remind me, at the top of the e-mail, that I asked you to do this. Then (preferably) paste the text into the body of an e-mail to me — or if that doesn’t work, attach it to an e-mail to me. I look forward to your story.”

I did as I was told and re-submitted the story his way.

No response. On August 9, 2000, I sent a follow-up query by e-mail.

In response that same day, they rejected the story and sent me a copy of their guidelines (which, of course, I’d had from the beginning). The editors felt the horror was effective, but that too little happened on stage, and the story had no supernatural element. They also mentioned that they were very heavily stocked and buying very little.

2. Second Submission: August 11, 2000

There’s a missing reply in my records, but the editor expressed interest and asked for a revision. I revised accordingly (overall tightening and making the ambiguous ending more clear) and re-submitted the story on October 30, 2000.

On November 29, 2000, the editor rejected the story: “Dear Mr. Durbin: I can’t remember if I got back to you about “Under the Tower of Valk,” which most likely means I didn’t. (Sorry about that — my workload is formidable right now.) Anyway, I think the new version is definitely less opaque at the end, but I’ve got to pass on it simply because the story doesn’t need to be fantasy. It could just as well be an historical story. [Yes, Chris, he wrote “an historical story.” Phooey!] (In fact, this explains in part my confusion over the ending in the previous draft — I was looking for a fantastic twist or aspect to the conclusion.) I do think it’s a good story, I just can’t use it in _____. You might try it out with ____ _____ at _____ Magazine or with ____ _____ at _____; I think it might fit into one of those magazines better than it does in _____. Meantime, I appreciate the revisions you made at my request and I’m sorry they ultimately didn’t pay off here. I hope I’ll see more from you soon.”

3. Third Submission: December 12, 2000 (I mentioned, of course, that I was submitting the story on the advice of the previous editor.)

No response. I sent a follow-up query by e-mail on April 27, 2001. (It was becoming more acceptable by then to do so.)

In May 2001, I heard that the editor’s significant other had passed away. I sent a letter of condolence. Never heard from the editor again.

4. Fourth Submission: June 4, 2001 (Submitted to the second editor recommended by Editor #2.)

On June 15, 2001, the editor sent me a nice e-mail saying he’d resigned as the editor of that magazine because the publisher could no longer pay him. He told me how to submit it to the right person, but he advised me that the publisher was really not buying now — was in deep financial trouble, etc.

5. Fifth Submission: June 21, 2001

Handwritten rejection on August 29, 2001, scrawled on the back of the bottom third ripped from my cover letter: “Thank you for submitting your story UNDER THE TOWER OF VALK to ____. Apologies for the delay in responding. It is not for us, I’m afraid. A striking line at the end but a [illegible word] middle passage that failed to convince: not sure the prisoner ever thought like that. Sorry.”

6. Sixth Submission: October 1, 2001

Rejection on January 21, 2002: Form rejection letter with two boxes checked: “We have considered your story, but find that it is not suitable for our publication.” — and then a long one about how they received a number of fairly good stories each month that just didn’t do enough original things, and this was one of those. But there was also a handwritten scrawl (which is generally a good thing to get): “This is more of a vignette, with very little to call it ‘SF’. We’re not sure why you have a flashback positioned between the two ‘present’ scenes. Doesn’t really suit us.”

At this point, it would have made very good sense to retire the story or else overhaul it in a major way. But I was keeping myself busy with other things, and I just wanted to keep trying with this one, which I thought was original and well-done. (I wrote “Under the Tower of Valk” at the same general time as “The Place of Roots.” I thought “Valk” was the stronger story, but “Roots” was snapped up by the first place I sent it — Fantasy & Science Fiction — and you can see what happened with “Valk”!)

7. Seventh Submission: February 4, 2002

Nice personal, handwritten rejection on March 5, 2002: “Dear Frederic, Nicely written piece that nearly makes it for us. In the end, I wasn’t completely won over by the ending. I’ll pass on it, but please do try us again soon.”

8. Eighth Submission: March 14, 2002

No response. Followed up by e-mail, and was asked to re-submit, which I did on July 25, 2002. It was rejected with a form letter in August 2002.

9. Ninth Submission: September 25, 2002

Very nice rejection letter on July 15, 2003: In part — “While we all found the writing excellent and the psychological study a compelling one, we don’t feel it’s suited for ____’s younger readers. In fact, we urge you to send this to an adult publication; it’s excellent writing, but it’s just not suited for our publication.” [Take an important lesson from that: I was getting desperate here, but don’t. If you think the story is probably wrong for the magazine, it probably is — it’s better not to waste your time or the editor’s.]

10. Tenth Submission: July 25, 2003

The story came back unread with a note that the magazine was on hiatus until sometime in 2004.

11. Eleventh Submission: September 26, 2003

Came back quickly and unread: too short for the anthology I’d submitted it to. [Take another lesson from this: do your homework and follow the rules. Again, I wasted my postage, my time, and an editor’s time.]

12. Twelfth Submission: October 10, 2003

Came back with a photocopied form rejection, no note, no signature.

13. Thirteenth Submission: January 29, 2004

The rejection came on March 29, 2004 with handwritten notes from three different editors:

A. “I really liked this story. The realism of the prisoner with no name, his thoughts so different than ours, his complete lack of recognition of what was happening. Your heart attack description was powerful, along with the unnamed prisoner’s complete ignorance of what a chair was or what another person’s arms would really feel like. The commander’s understanding and much too late compassion also moved me.”

B. “The opening was quite catchy. I think you started the story at the perfect place. I was disappointed when you switched to the “He who had no name” part. I had a very difficult time understanding the two stories. I couldn’t quite figure out how they were related. I needed more of a clue to the two parts. The conflict and resolution of the plot was really fuzzy to me.”

C. “This story had some great imagery. The scene where the prisoner escaped was great stuff. All the story really needs is a better plot line. At first I thought it was about the jailer and whether he’d be punished, then the plot suddenly turned to the prisoner and left me hanging. Why is the commander asking who killed the man when it’s obvious a breeze could’ve? Why does the commander suddenly turn to pity? Why is the jailer so afraid of him? What’s his reputation? Other than this your story really was quite good.” [Hee, hee, hee, hee, hee! I know that editor was trying to be kind and helpful with that last line, but isn’t it hilarious, in context? “Other than everything about it, your story is quite good!” — Thanks, I’m so happy to hear that!]

At this point I finally got the picture through my thick skull and did some serious revision of the piece.

14. Fourteenth Submission: April 12, 2004

The rejection came on May 6, 2004: form rejection to “Dear Contributor” saying that it wasn’t quite right for them, and that due to the overwhelming number of submissions they were receiving, the magazine was closing to unsolicited materials.

[Clarification here: “no unsolicited materials” doesn’t mean you don’t have a chance with that market or that you need an agent. It just means they don’t want you to send them a story they haven’t asked for. You can send them a query (formatted and worded properly, based on your study of their published guidelines). If they write back and say, “Yes, we want to read the story,” then you are sending them a “solicited” submission.]

15. Fifteenth Submission: August 12, 2004

Form rejection came back (postmark illegible): two boxes checked — the story lacked sufficient elements of the dark fantastic, surreal, bizarre, or strange, and the plot offered nothing new or interesting.

16. Sixteenth Submission: September 1, 2004

Undated form rejection came back apologizing for being a form letter and wishing me good luck.

17. Seventeenth Submission: September 18, 2004

Never heard a peep back from that editor . . . and by this point, I was tired of sending follow-ups for this story. I had pretty much come to the realization that other people didn’t like the idea as well as I did. And that’s also a lesson we need to learn, at some point, as writers. Not all our ideas are brilliant. Some, no matter how much we love them, may never really “work” for most other people. (I do think such cases, though, are the exception rather than the rule. Usually a story can be made reader-friendly with the right repairs.)

Don’t misunderstand the moral of this posting: I’m not advocating blind stubbornness. As a more mature writer than I was in 2000, I now know that I want my stories to appeal to most people who read them. You’re never going to please everybody, but if three or four knowledgeable readers have serious reservations — or if they think the story is, well, okay, but they’re clearly not wowed — then I believe it’s time to rethink and rewrite. So in a way, this little chronicle is a mini-course in What Not to Do. Don’t send one tired story around and around and around. That doesn’t mean get discouraged and hide the story in the bottom drawer. It doesn’t mean throw the story away. It means be open to suggestions. It means get feedback; rework the story until people are liking it . . . a lot.

“Under the Tower of Valk” was finally published in Ozment’s House of Twilight, Issue 7, Winter 2007. I know it was published chiefly because the editor is a friend of mine, which gained the story a kind, sympathetic reading. BUT it wasn’t a “mercy publication.” The editor has integrity, and he wouldn’t have published the piece if he hadn’t believed in it. And yes, before it went into print, I revised the story — very heavily.

This has been an extreme example. Most stories don’t get rejected this much, because one of three things usually happens: 1.) They’re good enough that they get accepted right away. 2.) The writers give up and stop submitting them, which is the saddest possibility. Or, 3.) The writers learn from the rejections they’re getting, revise accordingly, and the stories get accepted.

How do my books compare? I think The Threshold of Twilight had about as many rejections as “Under the Tower of Valk” did. I finally decided to stop working on it, since I knew it wasn’t publishable in its present state, and I was no longer the high-school and college student I’d been when I was writing it; there was nothing further I could do to make it publishable without writing an entirely new book — so I turned to writing entirely new books. Dragonfly had also garnered some 12-13 rejections, I think, before it hit the right editor at the right time.

So, the last words: Be open and willing to revise. And don’t give up!

Line-edits are going well here: I’m 75% of the way through the book!

This entry will, I hope, be more comment than posting. First, just to set the mood, here’s an excerpt from my story “Uther.” This “Fred” character isn’t me: he just happens to have the same name.

This entry will, I hope, be more comment than posting. First, just to set the mood, here’s an excerpt from my story “Uther.” This “Fred” character isn’t me: he just happens to have the same name.

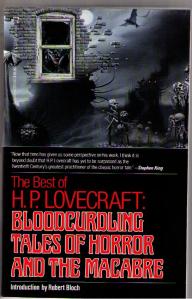

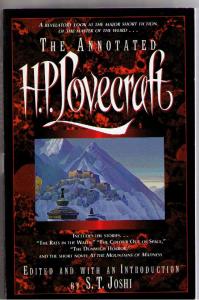

Then there’s H.P. Lovecraft. I think I’ve mentioned before how I used to see the covers of his books on the racks at our family bookstore, and they looked like the perfect books to me as a nine- or ten-year-old boy: hideous monsters, tentacles, crumbling stonework, etc. Oh, how I wish I had an image here of the very first cover that drew me to Lovecraft! I’m pretty sure it was a collection called The Dunwich Horror and Others. At any rate, the edition you read doesn’t matter too much, as long as it’s Lovecraft, and as long as you read enough stories to get a feel for him. I particularly recommend The Annotated H.P. Lovecraft, edited and with an introduction by S.T. Joshi. There’s also a More Annotated H.P. Lovecraft, annotated by S.T. Joshi and Peter Cannon. Although I’m talking October books here, my childhood recollections of Lovecraft are of the dusty back room of our bookstore, reading and drinking Pepsi with my knees propped up against the edge of the battered desk . . . and of reading him outdoors at

Then there’s H.P. Lovecraft. I think I’ve mentioned before how I used to see the covers of his books on the racks at our family bookstore, and they looked like the perfect books to me as a nine- or ten-year-old boy: hideous monsters, tentacles, crumbling stonework, etc. Oh, how I wish I had an image here of the very first cover that drew me to Lovecraft! I’m pretty sure it was a collection called The Dunwich Horror and Others. At any rate, the edition you read doesn’t matter too much, as long as it’s Lovecraft, and as long as you read enough stories to get a feel for him. I particularly recommend The Annotated H.P. Lovecraft, edited and with an introduction by S.T. Joshi. There’s also a More Annotated H.P. Lovecraft, annotated by S.T. Joshi and Peter Cannon. Although I’m talking October books here, my childhood recollections of Lovecraft are of the dusty back room of our bookstore, reading and drinking Pepsi with my knees propped up against the edge of the battered desk . . . and of reading him outdoors at  home on hot, hot summer days — heat and light all around me, heat waves shimmering in the fields, leaves whispering in the breeze — and in the pages, coldness and subterranean darkness, moldering crypts, secret rooms, sagging gambrel roofs in ancient New England towns. . . .

home on hot, hot summer days — heat and light all around me, heat waves shimmering in the fields, leaves whispering in the breeze — and in the pages, coldness and subterranean darkness, moldering crypts, secret rooms, sagging gambrel roofs in ancient New England towns. . . . During one of my first few summers in Japan, I found my way to the stories of Algernon Blackwood. In those years of my early twenties — a searching, angry, passionate, lonely, joyous, discovering time — I used to sit astride the seat of my parked bicycle on some forest trail near the sea, and in the green glow of filtered light, I’d read books. That’s where I read Blackwood’s “The Willows,” one of the scariest stories of all time. It was at around this time — 1990 or 1991 — that I had a very close brush with publication. A now-defunct small-press magazine titled Midnight Zoo expressed strong interest in my story “Iowa Mud,” but asked for revisions. I immediately subscribed to the magazine, revised the story, and sent it back. As I recall, they liked it still more, but wanted more revisions. So I obliged them. I loved reading the magazine — it was well put together, and the stories were right up my alley. They accepted the story, but before it saw print, they got into financial problems, as small-press magazines almost inevitably do. They asked if they could pay me in contributor copies instead of money, and I said sure. Then they ceased publication and disappeared altogether, and I never heard from them again. The story never made it into print. (Which may be a good thing.) [Oh — the point of telling about this near-publication experience {NPE} is that I sat around in that same pine forest revising “Iowa Mud,” so my memories of that time are all interwoven — my story, Blackwood, and Ambrose Bierce.]

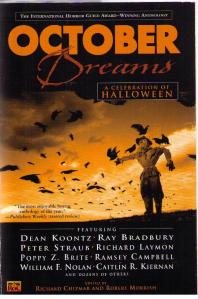

During one of my first few summers in Japan, I found my way to the stories of Algernon Blackwood. In those years of my early twenties — a searching, angry, passionate, lonely, joyous, discovering time — I used to sit astride the seat of my parked bicycle on some forest trail near the sea, and in the green glow of filtered light, I’d read books. That’s where I read Blackwood’s “The Willows,” one of the scariest stories of all time. It was at around this time — 1990 or 1991 — that I had a very close brush with publication. A now-defunct small-press magazine titled Midnight Zoo expressed strong interest in my story “Iowa Mud,” but asked for revisions. I immediately subscribed to the magazine, revised the story, and sent it back. As I recall, they liked it still more, but wanted more revisions. So I obliged them. I loved reading the magazine — it was well put together, and the stories were right up my alley. They accepted the story, but before it saw print, they got into financial problems, as small-press magazines almost inevitably do. They asked if they could pay me in contributor copies instead of money, and I said sure. Then they ceased publication and disappeared altogether, and I never heard from them again. The story never made it into print. (Which may be a good thing.) [Oh — the point of telling about this near-publication experience {NPE} is that I sat around in that same pine forest revising “Iowa Mud,” so my memories of that time are all interwoven — my story, Blackwood, and Ambrose Bierce.] My first novel Dragonfly was/is an ode to Hallowe’en. And speaking of that holiday: THE BOOK to read in this season (while you’re taking breaks from Dragonfly) is an anthology entitled October Dreams, edited by Richard Chizmar and Robert Morrish. What makes this one so wonderful is that it isn’t just a compilation of great Hallowe’en stories by a whole host of writers, some extremely famous, some virtually unknown — but it also includes, between the stories, mini-essays by many of the writers on actual memories of Hallowe’ens in their lives. If you read it, you may even decide you like the essays best of all. In fact, I’d love to see a whole book dedicated to that. Someone should solicit Hallowe’en memories from about fifty speculative fiction writers, ranging from the bestsellers to those in the small press — wouldn’t that be excellent? Anyway, in that book is my favorite short Hallowe’en story ever: “Boo,” by Richard Laymon. I won’t spoil it by giving away particulars, but I will say that this story captures pretty much everything I love about Hallowe’en. It’s beautiful and nostalgic; in places it makes you laugh out loud — partly at what’s happening, and partly at your own memories it evokes — it makes you ache with longing, not only for the Hallowe’ens of your youth, but for childhood itself — and, like any proper All Hallows tale, it packs a deeply disturbing wallop. “Boo,” by Richard Laymon — I dare you to find better! (And if you find better, please please pleeeease tell us about it here!)

My first novel Dragonfly was/is an ode to Hallowe’en. And speaking of that holiday: THE BOOK to read in this season (while you’re taking breaks from Dragonfly) is an anthology entitled October Dreams, edited by Richard Chizmar and Robert Morrish. What makes this one so wonderful is that it isn’t just a compilation of great Hallowe’en stories by a whole host of writers, some extremely famous, some virtually unknown — but it also includes, between the stories, mini-essays by many of the writers on actual memories of Hallowe’ens in their lives. If you read it, you may even decide you like the essays best of all. In fact, I’d love to see a whole book dedicated to that. Someone should solicit Hallowe’en memories from about fifty speculative fiction writers, ranging from the bestsellers to those in the small press — wouldn’t that be excellent? Anyway, in that book is my favorite short Hallowe’en story ever: “Boo,” by Richard Laymon. I won’t spoil it by giving away particulars, but I will say that this story captures pretty much everything I love about Hallowe’en. It’s beautiful and nostalgic; in places it makes you laugh out loud — partly at what’s happening, and partly at your own memories it evokes — it makes you ache with longing, not only for the Hallowe’ens of your youth, but for childhood itself — and, like any proper All Hallows tale, it packs a deeply disturbing wallop. “Boo,” by Richard Laymon — I dare you to find better! (And if you find better, please please pleeeease tell us about it here!) to those two mighty pillars of the horror genre, the vampire and the werewolf. . . . Several friends had been recommending to me the film Dog Soldiers (2001). It is a genuinely creepy and entertaining story, and it’s the sort that I think I may like better on subsequent viewings. (To be 100% honest, after the way so many trusted friends raved about it, I was a tiny bit disappointed on my first watching; it’s a good film, but it had a lot of hype to live up to. But I liked it enough that I’m talking about it here, aren’t I?) A group of soldiers on training maneuvers in the Scottish highlands end up trapped in an isolated farmhouse, desperately trying to hold off the werewolves until dawn. What I found at once surprising — and ultimately unsettling — about this movie was the lack of movement on the part of the werewolves. I believe (don’t quote me on this; I could be wrong) that they were depicted by using people in costumes — people in unnatural postures, on stilts, perhaps; and given all that, the actors actually had very limited mobility. There’s almost no lunging or pouncing. What we have are instantaneous glimpses of nearly motionless werewolves — monsters frozen in terrifying silhouettes, looming in the shadows. And whether intentionally or not, this taps right into our childhood fantasies and nightmares. Think about it: as kids, the imagined images that scared us the most weren’t lunging enemies — they were the things that lurked . . . that watched us from the shadows . . . that towered over our beds. Capitalizing on that fear, Dog Soldiers delivers quite a bite!

to those two mighty pillars of the horror genre, the vampire and the werewolf. . . . Several friends had been recommending to me the film Dog Soldiers (2001). It is a genuinely creepy and entertaining story, and it’s the sort that I think I may like better on subsequent viewings. (To be 100% honest, after the way so many trusted friends raved about it, I was a tiny bit disappointed on my first watching; it’s a good film, but it had a lot of hype to live up to. But I liked it enough that I’m talking about it here, aren’t I?) A group of soldiers on training maneuvers in the Scottish highlands end up trapped in an isolated farmhouse, desperately trying to hold off the werewolves until dawn. What I found at once surprising — and ultimately unsettling — about this movie was the lack of movement on the part of the werewolves. I believe (don’t quote me on this; I could be wrong) that they were depicted by using people in costumes — people in unnatural postures, on stilts, perhaps; and given all that, the actors actually had very limited mobility. There’s almost no lunging or pouncing. What we have are instantaneous glimpses of nearly motionless werewolves — monsters frozen in terrifying silhouettes, looming in the shadows. And whether intentionally or not, this taps right into our childhood fantasies and nightmares. Think about it: as kids, the imagined images that scared us the most weren’t lunging enemies — they were the things that lurked . . . that watched us from the shadows . . . that towered over our beds. Capitalizing on that fear, Dog Soldiers delivers quite a bite! But far and away the best movie I saw this summer, irrespective of genre, was the vampire film Let the Right One In. It’s a Swedish film, so you have the option of watching it either in Swedish, with English subtitles, or dubbed into English. So far I’ve watched it once each way, and there are things I like better about each version. It’s dark, haunting, beautiful, sad, and it uses the canon of vampire mythos to help us ask some profound questions. Some critics call it a “fairy tale.” Perhaps. Again — without giving too much away — it’s the story of the bonding and love between two lonely children — one living, one a vampire. It’s skillful and subtle, and it’s so thought-provoking that some of us discussed it for weeks after I saw it.

But far and away the best movie I saw this summer, irrespective of genre, was the vampire film Let the Right One In. It’s a Swedish film, so you have the option of watching it either in Swedish, with English subtitles, or dubbed into English. So far I’ve watched it once each way, and there are things I like better about each version. It’s dark, haunting, beautiful, sad, and it uses the canon of vampire mythos to help us ask some profound questions. Some critics call it a “fairy tale.” Perhaps. Again — without giving too much away — it’s the story of the bonding and love between two lonely children — one living, one a vampire. It’s skillful and subtle, and it’s so thought-provoking that some of us discussed it for weeks after I saw it.