We’re entering a new era here: this marks the 101st posting on this blog. That’s right: there have been 100 so far. That does not seem possible, does it? We’re opening a new pack of a hundred.

This blog is too nice a thing to let languish or evaporate. By “nice,” I don’t mean my posts: I mean this gathering of friends. Part of my struggle during this long silence has been that I’ve felt I’ve said everything I can possibly say about writing. I’ve told my stories. I’ve asked my leading questions, and we’ve had some great discussions and wonderful times. I was seriously feeling that a blog is a thing with a limited lifespan, like every other creature that breathes upon the Earth, and I was thinking that maybe this one had come to its end.

But there are always new stories to tell, right? Let’s forge ahead and see. There may be more undiscovered rooms down this dark corridor. There may be another valley beyond this ridge, and another ridge beyond that. The road, as we noted in the very first entry, goes ever on, and it is not for us to decide where it ends. Though we curl up under a tree to sleep the sleep of exhaustion, there comes a time when squirrels throw nuts on our heads, and it’s time to get up and walk again.

So let’s start with a writing update.

I started writing The Sacred Woods on April 23rd of last year (the possible birthday of the possible man who may have been Shakespeare). I started writing my new novel, The House of the Worm, on April 22nd of this year. This is my season for starting books. Chaucer was right: it’s the month for starting pilgrimages.

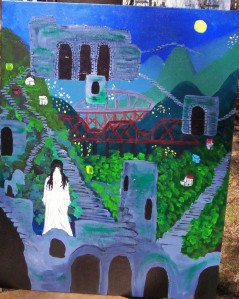

Doing some quick math here: I’m about 5,500 words into the draft of The House of the Worm (hereafter designated as THOW) [you can pronounce it either as “though” or as “thou”–it’s up to you]–and I’m truly excited about it. What keeps us writers going is the belief that this is the one: this is the best thing by far that we’ve ever done, and it’s the one that will reach the masses, and it’s the one we’ll be remembered for. We go through that every time, even if we’re writing a short story. But that’s good. As my good and wise friend Marquee Movies has said, “You’re on a path. Keep breaking new ground. Keep striving to be the best writer you can be.” And as marching band leader Mr. Smith (whom I’ve quoted before) said, keep doing the halftime marching show better every time you do it. I can honestly say with THOW that I’m breaking new ground (for me), and it feels very, very good. As for the content: all I can tell you right now is to look back at the previous posting. See those two paintings entitled The House of the Worm (I & II)? Those were a large part of the inspiration. . . . and so were several other things. As usual, various disparate elements have coalesced into a book idea.

The Sacred Woods (TSW) has gone forth and been rejected by most of the greatest editors in the business. (How’s that for name-dropping?) My agent has been valiant and amazing in getting it read by all sorts of top-drawer people, and it’s been both exhilarating and frustrating to hear about their reactions. Ninety-five percent of them have gone WAY out of their ways to write wonderful, heartfelt rejection letters about how much they loved the book, how they lost sleep all weekend and ignored their piles of work to finish reading it, even though they knew they were going to have to turn it down. The fifteen or so young-adult editors mostly said they themselves loved it, but they thought it was too adult for their lists — it would go over kids’ heads. We’ve heard back from two adult editors so far who have said they loved it but that it falls through the cracks between children’s fiction and fiction for grownups.

Don’t you wish we lived in a society in which labels weren’t important? I ask you: when you find a book you love, do you care what part of the bookstore you bought it in? I wish more publishers would care less about pigeonholes. “This book I’m crazy about, it — what? You say it’s a children’s book? — Oh. Well, then, forget what I said. I don’t like it so much after all.”

One editor, complaining about the narrator’s voice (at times very young, at times more young-adult), popped out with, “but I’m not always right. I had a problem with the narrative voice of The Lovely Bones, too, and we all know how that turned out.”

So, yeah. That’s the report on TSW. It’s a good book that no one can buy, which is exactly what Dragonfly was — except Dragonfly had some scary elements, so Arkham House bought it. But TSW is still out there: it’s really just begun its rounds of adult editors, so there’s still plenty of hope. All it takes is one. Another wise friend pointed out that what TSW is is “a British children’s book” — which really makes sense. In the U.K., a proportionately larger number of kids are still taught the love of reading. My agent is looking into possibilities there, too.

“Glory Day” (the story, not the poem) is still under consideration at Cicada.

As far as I know, The Star Shard is still scheduled for a Fall 2011 release from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. I’m currently waiting for the editor to send me her revision notes so that I can overhaul the manuscript. At last report, she was swamped with her Spring 2011 books and hadn’t yet started on Fall.

Agondria came back from the respectable Canadian publisher who had been very seriously considering it. I bounced it next off a likely U.K. publisher who turns out to be currently closed to submissions. The editor of Black Gate had requested a look at more of the stories, so currently I’m giving him a chance to read them. One of the stories is scheduled to appear in the very next issue of Black Gate — Issue #15 — this fall, under the title “World’s End.”

So anyway, the new school year is three weeks underway. For the first time ever, I have a Russian student, a Spanish student, and a French student among my Japanese students. (I love how, in a French accent, the World Wide Web is pronounced “ze Ahntarnet”!) Seriously, it’s very good for all the students to have some additional accents and cultural perspectives. I’m grateful that those international students are there (in recent years, I’ve had students from China, Korea, Malaysia, and Vietnam, too).

The cherry blossoms are over, and we’re still shivering here. I hope some of you scientist types will explain to me just why this phenomenon is called “Global Warming” when every season is getting colder and colder.

I’ve been listening to Celtic/Irish/Scottish music — my latest discovery is a group called The Tannahill Weavers.

And finally, the movie awards: the first runner-up for Best Movie Recently Seen By Fred is District 9. This is what science-fiction should be like. Nothing is wasted: the writers knew exactly where to start and where to stop. It’s a very intelligent film, original and fresh in many ways.

And the hands-down winner: The Wolfman. I simply cannot say enough good things about this movie. Excellent storytelling, great casting and acting, brilliant directing — but the truly breathtaking elements are the sets and the lighting. Talbot Hall and the English countryside of the 1890s are a spectacle, an atmospheric extravaganza. I’ll go on record as saying that, for me, The Wolfman was more visually stunning and satisfying than Avatar, which I also enjoyed. But that’s just me! Give me spooky moors, rambling estates much declined from their former glory, Gypsy camps, and dark woods.

Honorable mention also goes to the musical Nine, which has much to say to us creative types — about our priorities, about how we should live. The last scene is unforgettable.

Oh, and the Australian film Rogue is definitely worth checking out — if, like me, you count Jaws among the half-dozen best films ever made.

As the Jeff Bridges character says in Crazy Heart: “It’s great to be back!”

Talk to you again soon.