This April saw the release of a new book certain to delight fans of H.P. Lovecraft and his Cthulhu Mythos stories. Edited by Darrell Schweitzer and published by DAW Books, Inc., the anthology is called Cthulhu’s Reign and includes stories by Ian Watson, Don Webb, Mike Allen, Ken Asamatsu, Will Murray, Matt Cardin, Darrell Schweitzer, John R. Fultz, John Langan, Jay Lake, Gregory Frost, Brian Stableford, Laird Barron, Richard A. Lupoff, and Fred Chappell. Cthulhu Mythos stories as Lovecraft wrote them (though he never used the term “Cthulhu Mythos”) foreshadow a time when the Great Old Ones — unspeakably monstrous beings that descended from the stars in a primordial age and are now sleeping in the deep places of the Earth and beneath the sea — will awaken, arise, and make the world their own. In Lovecraft’s tales, we catch glimpses of the cosmic horror in secretive cults, isolated New England towns (redolent with rotting gambrel roofs and moldering crypts), ancient dusty tomes, and strange human-monster hybrids who are the firstfruits of horrors to come.

This April saw the release of a new book certain to delight fans of H.P. Lovecraft and his Cthulhu Mythos stories. Edited by Darrell Schweitzer and published by DAW Books, Inc., the anthology is called Cthulhu’s Reign and includes stories by Ian Watson, Don Webb, Mike Allen, Ken Asamatsu, Will Murray, Matt Cardin, Darrell Schweitzer, John R. Fultz, John Langan, Jay Lake, Gregory Frost, Brian Stableford, Laird Barron, Richard A. Lupoff, and Fred Chappell. Cthulhu Mythos stories as Lovecraft wrote them (though he never used the term “Cthulhu Mythos”) foreshadow a time when the Great Old Ones — unspeakably monstrous beings that descended from the stars in a primordial age and are now sleeping in the deep places of the Earth and beneath the sea — will awaken, arise, and make the world their own. In Lovecraft’s tales, we catch glimpses of the cosmic horror in secretive cults, isolated New England towns (redolent with rotting gambrel roofs and moldering crypts), ancient dusty tomes, and strange human-monster hybrids who are the firstfruits of horrors to come.

Lovecraft’s stories look ahead to this time “when the stars are right” and “the Earth will be wiped clean.” For the most part, very few of the multitude of writers who have added to the Mythos in the years since Lovecraft have tackled the question of what the world will be like after sunken R’lyeh rises from ocean depths and Cthulhu begins his squamous reign. (A noteworthy exception is Neil Gaiman’s story “A Study in Emerald” in his collection Fragile Things, which presents a most unique take on Sherlock Holmes and the royal families of the world.)

Lovecraft’s stories look ahead to this time “when the stars are right” and “the Earth will be wiped clean.” For the most part, very few of the multitude of writers who have added to the Mythos in the years since Lovecraft have tackled the question of what the world will be like after sunken R’lyeh rises from ocean depths and Cthulhu begins his squamous reign. (A noteworthy exception is Neil Gaiman’s story “A Study in Emerald” in his collection Fragile Things, which presents a most unique take on Sherlock Holmes and the royal families of the world.)

This anthology steps into the breach. As its title suggests, the stories take us to a world in which Cthulhu is no longer sleeping.

One of the writers, John R. Fultz, graciously agreed to answer my interview questions here. (You may recall that he chatted with us on this blog in November of last year, in the post called “Pen and Sorcery: An Interview with John R. Fultz.”)

My apologies for some slight redundancies: I sent John all the questions first, and in a few cases his earlier answers partially address later questions. I didn’t want to alter what he actually said, so everything is presented here in full. (Just so you know the instances of repetition are not a case of my not listening!)

1. First of all, the table of contents of this anthology reads like a hall of fame. Every writer here is a recognizable name in the industry; many of them have been hugely successful and have produced award-winning fiction for years. How did you feel when Darrell Schweitzer asked you to contribute a tale?

I was totally honored by the chance to be in this book. Darrell mentioned it and wasn’t sure if he had any more room for additional stories, so I wrote one that wasn’t terribly long. It was the story itself that drew his final “Yes.” If I had written something he didn’t feel was good enough for the book, I know he would have told me. So I was elated when he accepted “This Is How the World Ends.” This is such a great anthology, I’m really proud of it.

I was totally honored by the chance to be in this book. Darrell mentioned it and wasn’t sure if he had any more room for additional stories, so I wrote one that wasn’t terribly long. It was the story itself that drew his final “Yes.” If I had written something he didn’t feel was good enough for the book, I know he would have told me. So I was elated when he accepted “This Is How the World Ends.” This is such a great anthology, I’m really proud of it.

2. Most of your previous work has been fantasy, not horror. How far back does your interest in Lovecraft’s Cthulhu stories go? [I was drawn to the books in about 5th or 6th grade by the delightfully horrendous covers on the paperbacks in our family’s bookstore.] Can you remember how you first encountered them and what your reaction was?

I don’t recall reading my first Lovecraft tale, but I believe the first HPL book I

ever read was THE DOOM THAT CAME TO SARNATH AND OTHER STORIES. Followed by THE DREAM-QUEST OF UNKNOWN KADATH. I’m talking about the Del Rey Lovecraft series with the amazing Michael Whelan covers (see attached images). I’m not sure exactly which one came first, but a friend of mine in high school was reading these and recommended them. It was the exquisitely creepy cover art that got my interest. And when I read stories such as “The Doom that Came to Sarnath,” “The Other Gods,” “Polaris,” “Ex Oblivione,” and the beautiful “Quest of Iranon,” I became an instant fan. They were fantasies unlike anything else I had experienced at the time: lyrical, poetic, full of brilliant images and mythic grandeur, with a current of subtle horror reminiscent of the best dreams and nightmares.

That’s when I started looking for anything by Lovecraft…and that lead me to THE DREAM-QUEST collection. “The Dream-Quest of Uknown Kadath” absolutely blew my mind, and that book also featured the magnificent stories “Celephais,” “The White Ship,” “The Silver Key,” and the stunning “Through the Gates of the Silver Key.” Lovecraft’s cycle of “Dunsanian” or “Dreamlands” stories remain my favorites of all his works. Some purists decry that part of his body of work as less exceptional than his more “pure” horror…but I disagree. Another terrific thing about these stories is that they led me to the spectacular fantasy work of Lord Dunsany, who was one of Lovecraft’s literary heroes (and with good reason). Some see these tales as Lovecraft simply “trying to be Dunsany,” but I see them as a vital part of Lovecraft’s output…and even though they are fantasy they are laced with the elements of cosmic horror that infuse the rest of his work.

So my HPL fanhood began with these two books, but led me to the other books in the series, all bearing gorgeous Michael Whelan covers: THE TOMB AND OTHER TALES and AT THE MOUNTAINS OF MADNESS AND OTHER TALES OF TERROR. Finally, during my first year of college (’87-’88) I discovered August Derleth’s THE TRAIL OF CTHULHU, which entertained me to no end. It was a perfect blend of pulp adventure and Lovecraft fiction. I remember really enjoying this story of Professor Laban Shrewsbury and his colleagues seeking out the Black Island where Cthulhu was soon to rise. Still, when it comes to Lovecraft, nothing beats the stories in those first two collections for me…although “At the Mountains of Madness” is also a favorite.

[Fred here: “The Quest of Iranon” was a big influence on my story “The Place of Roots” (Fantasy & Science Fiction, February 2001). I was also enchanted with Lord Dunsany as a teenager. But I must confess I have never really delved into Lovecraft’s “Dunsanian” or “Dreamlands” stories. I think I’ve read pretty much everything else of his, and my favorites are the “witchy” New England stories, with the secret attic rooms, the impossible angles, the swamps full of croaking frogs, and the people that are not quite people. I love how, rare as the forbidden Necronomicon is, copies seem to turn up everywhere, just when some innocent character is enjoying too much sanity. Oh — and for me, the Michael Whelan covers are beautiful, but they represent the Lovecraft of my twenties and thirties. The Lovecraft I devoured in my childhood had the Great Old covers — the incomparable Gervasio Gallardo and some other artists whose names I never knew. I wish I had those books here so I could scan the covers and offer glimpses!]

3. Reading “This Is How the World Ends,” I was deeply impressed that you were able to tell a story in a contemporary voice, a modern setting, that also felt quite true to Lovecraft’s intentions and sensibilities. Did your editor give you any specific guidelines concerning what your tale should or should not be?

No, Darrell simply told me the “hook” of the anthology, i.e. that it involved stories set after Cthulhu and the Old Ones rose up to reclaim the earth (or “wipe it clean” as the case may be). From there I was free to pursue my own Lovecraftian muse. Darrell is one of fantasy’s Truly Great Editors, and that’s what truly great editors do — they get out of the way and let writers write. I decided to go in a very survivalist, post-apocalyptian vein. I didn’t want the typical scholars trudging through libraries or detectives tracking cultists. I wanted to see how an “Average Joe” would survive when these preposterous space-gods started crushing humanity into pulp. My initial thought was “Sort of like TERMINATOR with giant monsters instead of robots…”

[Fred here: It’s excellent that your character was meant to be an “Average Joe,” and his name actually is “Joe”!]

4. And in a related question: was there some back-and-forth between you and the editor as you revised your story? Did he ask for changes, or did he pretty much trust you all to produce polished stories on your own?

Darrell handled all his editing on a case-by-case basis. I had no knowledge of his process with other writers. But most of them were people he invited to participate, so knowing Darrell I’m pretty sure he didn’t mess with their writing processes very much. Again, the sign of a terrific editor. In the case of my finished story, he didn’t ask for a single change as far as I remember. Of course, he’s been a fiction mentor for me for many, many years, so over the course of our friendship he’s taught me how to write the best possible story I can. We’ve known each other for over twenty years, although we didn’t meet face-to-face until a few years ago at the 2006 WorldCon (where he actually introduced me to Harlan Ellison!…I was dumbstruck.).

5. When you set out to write this story, were there any particular aspects of Lovecraft’s vision and style that you wanted to maintain or perhaps explore further? Was there a specific quote or passage that you kept before you as a guide? And, without giving away your plot, is there a dimension to the vision that you added, that is uniquely your own? What is the John Fultzness of this story?

Ha! “Fultzness”…I love that, Fred. Let’s see…the aspect that I wanted to explore was the sheer monstrosity of HPL’s creations…I wanted to dive deep into “monster tale” territory and let the blood and slime fly. In this I was probably inspired by Mike Mignola’s terrific HELLBOY and B.P.R.D. comics — which are very Lovecraftian and visually brilliant. Many of the other authors went into the depths of sheer “strangeness”…exploring the metaphysical, cosmic, and spiritual side of Cthulhu’s Reign…but I chose to take a more direct route to horror. This was a conscious choice…I wanted it to feel almost like a western. I did do some research about what HPL said would actually happen when the Old Ones returned and took back the planet, then I let my imagination run wild. If I added anything that is uniquely my own, it might be that I filtered my twelve years as a Californian into the story. I wanted to write a “West Coast Cthulhu Apocalypse Western Survivalist Horror Tale.” I guess I did that. If I did it all over, I might go in a more metaphysical or cosmic direction…but I still like the way this story flies in the face of all that phantasmal stuff by staying “down to earth” until the final scene.

[Fred here: That’s fascinating! Lovecraft’s stories are mainly focused on the East, on New England. You took things out West, and yes, as I read the story, I noticed how Californian it is. I was thinking, “I’ll bet he’s actually been to all these places.”]

6. Lovecraft wrote his stories in the 1920s-’30s. Since that time, generations of writers have produced an uncountable number of Cthulhu Mythos tales, some faithful to Lovecraft’s vision, some horrendously not so. If one adds in the fiction more generally influenced by the originals, the number of Lovecraft-inspired stories increases exponentially. There are Lovecraft scholars who have written dissertations on him; there are lifelong fans who know every detail of his stories — and you knew such people would read this anthology. Given all that, was it daunting to write a Cthulhu Mythos story? Did it come easily? How did you set about the task?

Actually, it did come rather easily because I didn’t really think of it as a “Cthulhu Mythos” story…I thought of it more as a Survivalist Horror story with Western elements…and of course, Lovecraft elements. This is one reason I wanted a protagonist who was as far removed from the Cthulhu Mythos as possible…not a professor, or occultist, or other typical Lovecraftian character. Just an average, everyday American (albeit, a war vet), who has to deal with a World Gone Mad. Once I had a firm handle on my character, Joe, the story began to write itself. The driving theme was SURVIVAL. That is Joe’s goal throughout the entire story…how do you survive in a world that is essentially un-survivable? This story is the answer to that question.

7. Your protagonist is a military veteran, a man who has known loss and disillusionment, but he’s a determined survivor. (He’s quite different from the typical protagonists Lovecraft chose!) Was that a conscious deliberation on your part, or did that character just come to you whole cloth from the beginning?

Yes, very conscious choice, as I described above. Since I wanted to explore the concept of SURVIVAL, I needed a protagonist who literally knew how to survive. Those brave men and women who go fight their countries’ battles know all about surviving in a world gone to hell. So a vet seemed a natural choice for the soft-spoken “badass” that I needed for this story. Joe was inspired to a large degree by some of the farmers I encountered in the San Joaquin Valley (central California’s “salad bowl”), which ironically reminded me of the farmers I had known back in my native state Kentucky. Farmers are tough folk…a farmer who is also a veteran…that is someone who will survive. Remember that old Hank Williams Jr. song “A Country Boy Can Survive”? That could actually be the theme song of this story. I’ll remember that when it’s optioned as a movie. 🙂

[Fred here: Your Joe is certainly no pale young man given to bouts of melancholy and inclined to sit up far into the night poring over eldritch texts.]

8. Somewhat related (and this is more of an observation than a question): in Lovecraft’s tales, the conflict is almost never physical. It’s a battle against gradually-awakening, often unwanted awareness. The character goes to an unfamiliar place, uncovers information (willingly or unwillingly), and the knowledge comes at a terrible cost. In your story, there’s no “uncovering of forbidden knowledge” to be done. There’s no need for a copy of the Necronomicon. The Old Ones are back, and their presence is unmissable. The conflict becomes, at least on the surface, very physical. (Your story doesn’t stop at the surface, though.) Any thoughts on this? (Again, I haven’t given you a question to answer . . . so you’re entitled to say “Yes, Chris Farley, I remember that. Yes, I liked it.”)

Chris Farley reference! Nice…

Your observation is spot-on. I wanted to write a story that would defy all that “forbidden knowledge” and “esoteric mysteries” rigamarole and take a more direct route. I mean, after all, this is a world where A GIANT SQUID-GOD FROM SPACE HAS RISEN FROM THE OCEAN AND CONQUERED THE WORLD! There aren’t many mysteries left at this point! When terrors lurk in the shadows and awful secrets are learned from ancient tomes, you are in Lovecraft territory…but in this anthology all bets are off. CTHULHU has won. It doesn’t matter what you do…what you know…you’re in the same boat as every other shlub. So even though some of the other stories in CR really boggled my mind, I’m glad my story was more of a knuckle sandwich than a terrifying thought.

9. Your editor, Darrell Schweitzer, is a living treasure of our genre(s) [fantasy and horror]. He coedited Weird Tales for years and won a World Fantasy Award for it. He’s written and edited a very long shelf-load of amazing books and given us “about three hundred short stories, hundreds of essays, reviews, and poems” (I’m quoting from the bio notes). He even writes Cthulhu limericks and will recite them if provoked. For all this, in my firsthand experience, he’s always willing to talk to “the little guy,” to encourage the relatively unknown writer. What was it like working with him?

I love Darrell. He is an unsung genius. I don’t say this because he’s a friend

of mine. I knew it before I ever met him. Back in ’89 when I picked up a copy of WEIRD TALES and read his story “The Mysteries of the Faceless King” I became an instant fan. I set out searching for any stories of his I could find. Every one of his story collections is full of timeless, glimmering prose jewels. Like Clark Ashton Smith and Robert E. Howard, he’s also an amazing poet…which is probably why his prose is so lyrical and engaging. I consider him one of the Greatest Living Fantasy Writers, although he gets more attention for his critical/essayist/editor role. Anyone who takes the time to explore his back catalog of story collections and read MASK OF THE SORCERER will see what I’m talking about. He’s an author that EVERY fantasy fan should be reading.

As you mentioned, in addition to being a literary genius, Darrell is also one of the nicest guys you could ever meet. His sense of humor is staggering…he may be the biggest Three Stooges fan I ever met. And he really knows how to give writing advice that works. I started sending story submissions to WEIRD TALES many years before I was ready to be published…I was a sophomore at the University of Kentucky, writing fantasy tales in my Creative Writing class and sending them to WT. Darrell always gave me the greatest responses and told me how to improve my writing, unlike most other rejections I got early in life, which were basically just form letters. Darrell was extremely encouraging to me as a young writer…which meant a lot to me because he was already one of my favorite writers. And still is. I knew that, someday, if I could only write a story that was good enough for Darrell Schweitzer, I could call myself a Writer. That day finally came in early 2004 when he accepted my story “The Persecution of Artifice the Quill” for WEIRD TALES. It appeared in WT #340. Until that time I had only really been published in small-press mags.

[Fred here: About Darrell’s sense of humor: I remember talking with him at a very late hour at a World Fantasy Con, and from his pocket he pulled a collection of rare, ancient coins and explained that he was a “dealer in bargain-rate antiquities.”]

10. I don’t think there are many who would dispute the claim (I’m quoting Mr. Schweitzer here, in his introduction) that “Lovecraft (1890-1937) was the greatest writer of weird and horrific fiction in English in the 20th century.” Why do you think Lovecraft’s impact has been so enormous? What is his appeal? Why do you think he’s still being read, when so many writers from the pulp era have become historical footnotes?

Who can say why an author truly achieves immortality? It might be the sheer quality of his work. It might be the cult-like devotion of his fans and readers (and all their work to preserve his legacy). I do think the appeal of Lovecraft’s fiction is a universal one…fear being the oldest emotion…and the power of his writing is so great that it rises above outdated diction, verbiage, and style. Just like the work of Edgar Allen Poe does. It’s the STORIES that are so good, we don’t mind the “old-fashioned” style in which they are told. With Lovecraft, as with many other fantasy/horror authors, that antiquated style is actually part of the charm. I also think his appeal lies in how he merged fantasy and horror in unique and expansive ways that opened new doors for other writers. Howard and Smith were so inspired by HPL’s stories, they started writing tales set in his universe! That tells you something right there.

11. Although your story is gruesome and horrific (as a Cthulhu story ought to be), your language often reads like poetry — descriptive, vivid, and understated, leaving much to the reader’s imagination. To quote: “. . . something big as the moon crawled out of the ocean.” It amazes me that a mere half-sentence can be at once beautiful and terrifying. And this part: “A single day and all the major cities . . . gone.” I couldn’t help hearing an echo of Plato’s description of how Atlantis was destroyed in “a single day and night of misfortune.” Do you have any thoughts about the relationship of poetry to tales of the strange and terrible?

Oh, definitely. Most of my favorite writers (especially fantasy and horror writers) were also poets. Poetry is the bare distillation of words…the sheer essence of words themselves…it requires a mastery of imagery and word choice. Every word matters MORE because there are so few of them. Even a long poem has waaay less words than a short story. Poetry cuts right to the heart of what makes fantasy and horror work: effective imagery and the joy of language. I never considered myself a poet…but I try to achieve a lyrical quality in my prose. The fact that I wrote songs for many, many years does help, songs and poetry being closely related. But I think it’s more a matter of being aware of metaphor, simile, and figurative language. Using those well is far more effective than throwing in a bunch of adjectives. It’s all about creating images in your reader’s mind by appealing to the five senses…as well as the spiritual sensations. Robert E. Howard was a terrific poet, and Clark Ashton Smith (despite his tremendous verbosity) was as well. Their stories sing with lyrical imagery that brings their fantasies to life. So there is definitely a link between prose and poetry, especially in the realm of weird/fantastic fiction.

[Fred here: This reminds me that John has also written a series of excellent articles on the craft of writing fantasy. His blog is in my blogroll over there at the right. Click on that, and you’ll get to his blog; from there, I think you can find links to the Black Gate website where his articles are.]

12. Do you have a favorite among Lovecraft’s stories? [I would be hard pressed to choose just one, though I think I could single out four or five. Is that an oxymoron, “singling” out “four or five”?]

That is tough. I think I would have to choose “The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath.” It’s sort of the crown jewel of his “Dunsanian/Dreamlands” stories…which are my favorite HPL tales.

[Fred here: For atmosphere, I love “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” “The Dunwich Horror,” and “The Dreams in the Witch-House.” I believe “The Strange High House in the Mist” completely supersedes genre and should be included in the English lit survey texts used in colleges and universities. My #1 favorite HPL story just might be “The Shunned House,” because in a way it encapsulates the cosmic horror of Lovecraft much as John 3:16 encapsulates the Gospel.]

13. Finally, what’s next for John R. Fultz? What’s out, what’s coming out, and can you give any hints about what you’re working on? I believe your epic fantasy graphic novel Primordia is due for release in a complete, remastered, beautiful edition very soon. Would you care to tell readers why they should rush out and get it, and where to do so?

The PRIMORDIA graphic novel is a “stone-age faerie tale” written by me, beautifully drawn by Roel Wielinga, colored by Joel Chua, and published by Archaia Comics. It is truly a feast for the eyes, and anyone who likes epic fantasy will dig the story. It combines everything I’ve ever loved about fantasy in the comics medium…and the hardcover includes a new short story from me called “The Tale of the Dawn Child,” as well as a lot of other extras.

I have a really cool wizard story called “The Thirteen Texts of Arthyria” coming up in THE WAY OF THE WIZARD, an anthology coming in November from Prime Books. This one will be packed with “big-name” fantasy writers like Neil Gaiman and George R.R. Martin, to name a couple.

My story “The Vintages of Dream” should be appearing in the very next issue of BLACK GATE, and I have a new tale called “The Gnomes of Carrick County” slated for an upcoming issue of SPACE AND TIME.

[Quick interruption from Fred: My story “World’s End” should be in that very same issue of Black Gate, so everyone: that’s the issue to get, this fall, BG #15!]

This October LIGHTSPEED, the new online science-fiction magazine from John Joseph Adams, will be featuring my sci-fi/horror story “The Taste of Starlight.” It is the most disturbing and horrific thing I’ve ever written…just in time for Halloween. Can’t wait!

I’m currently working on a novel that blends high fantasy with Native American adventure fiction to create something that is neither. Tentative title: THE LIFE AND DREAMS OF TALL EAGLE.

John, thank you so much for your time and for agreeing to do this interview!

Thanks, Fred!

This is Fred again: for those of you who are wondering how to pronounce “Cthulhu”: I remember reading Lovecraft’s specific explanation. It must have been in one of his letters, though I don’t remember which one or to whom. He explained that it was meant to be a representation of a name produced by a physical speech mechanism not even remotely human. It’s a use of our alphabet to approximate an utterly alien utteration. That being said, Lovecraft pronounced it by saying “Kluh-loo,” two syllables, with the first being extremely guttural. Just pretend you’re a colossal squid from space, and say what feels natural.

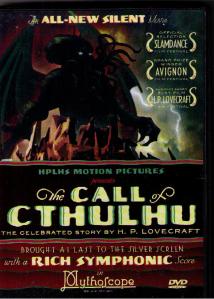

There is also a Lovecraft-based movie that those who appreciate his fiction should know about. In 2005, the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society released a labor of love . . . and craft, heh, heh (25 cents to the Pun Fund) . . . called

The Call of Cthulhu, a film version of his story by that title, which is one of the three key stories for understanding the Cthulhu Mythos (the other two being

The Dunwich Horror and

The Shadow Over Innsmouth). What sets this movie apart and makes it rise (like sunken R’lyeh) over the morass of mostly poor attempts to bring Lovecraft tales to the screen is that the filmmakers took great pains to create a movie that might have been made in Lovecraft’s day. It’s silent and black-and-white, very carefully made to look like a vintage relic of the early thirties — yet behind the grainy, authentically-primitive presentation are state-of-the-art techniques. A bunch of people worked really hard, knowing what moviemakers know

now, to produce a stark, haunting 47-minute movie that looks for all the world like it was made

then. And this, I truly believe, is the way to bring Lovecraft’s Mythos to a visual medium. This is the HPL Historical Society, so they’re sensitive to what his stories are supposed to feel like, what is important about them, and what oughtn’t to be sacrificed. There are abundant special features in full color, which are every bit as much fun as the movie itself. I am a discriminating buyer of DVDs: I try to buy only ones that I’m pretty sure I’ll watch again and again. And I consider this one to be a good investment.

By the way, you’ve gotta love the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society’s motto: Ludo Fore Putavimus. They claim that’s Latin for “We Thought It Would Be Fun.”