First: We are nearly through the Netflix series Stranger Things. Loyal kid friends on bicycles in the eighties, romance, a monster, mysterious nights in the Midwest, references to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, not one but TWO typewriters and a D&D session in the first episode — what’s not to love?!

Okay — home movies: who remembers ’em? Eight millimeter cameras . . . fifty-foot reels that had to be flipped over in the middle, in as dark a place as you could find. Let’s go on a journey into memory . . .

A week or so after the county fair one year, my mom bought hot dogs on sale and had a wiener roast for the cousins on Dad’s side of the family, who’d asked if they could come and watch home movies. It was something they wanted to do every few years; Dad had always been the chronicler of events—the one who brought along a camera to every gathering. He’d long since switched to video, then digital; but the movies that held the deepest fascination were the old ones, those from the era of silent eight millimeter film.

At full dark, the movies began in the living room. I was the projectionist now, Dad having turned over all the equipment to me. But Dad still governed the proceedings, ensconced in his recliner.

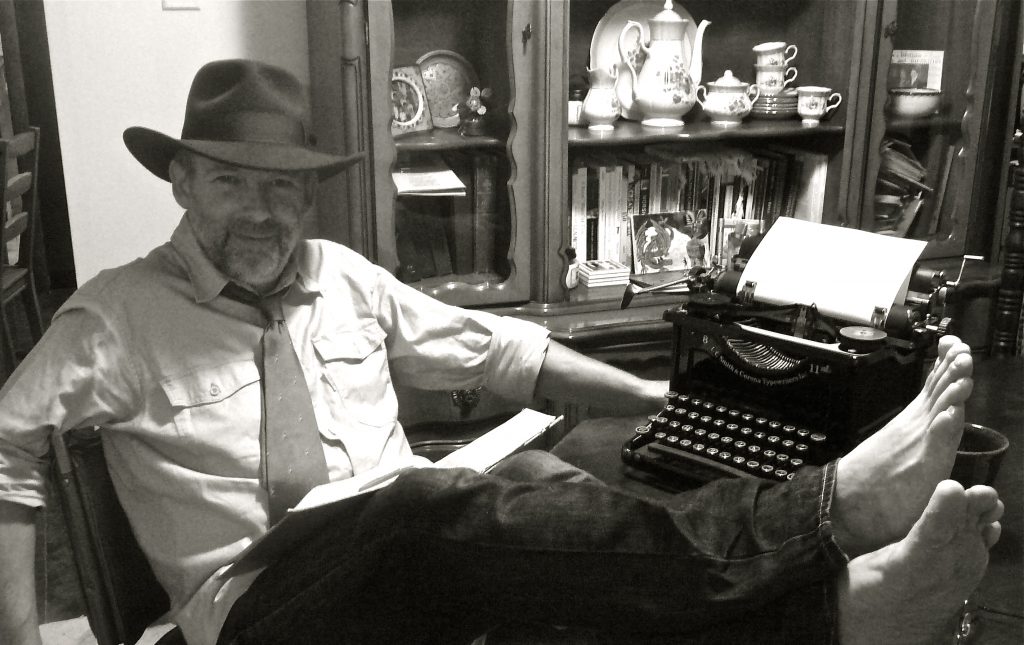

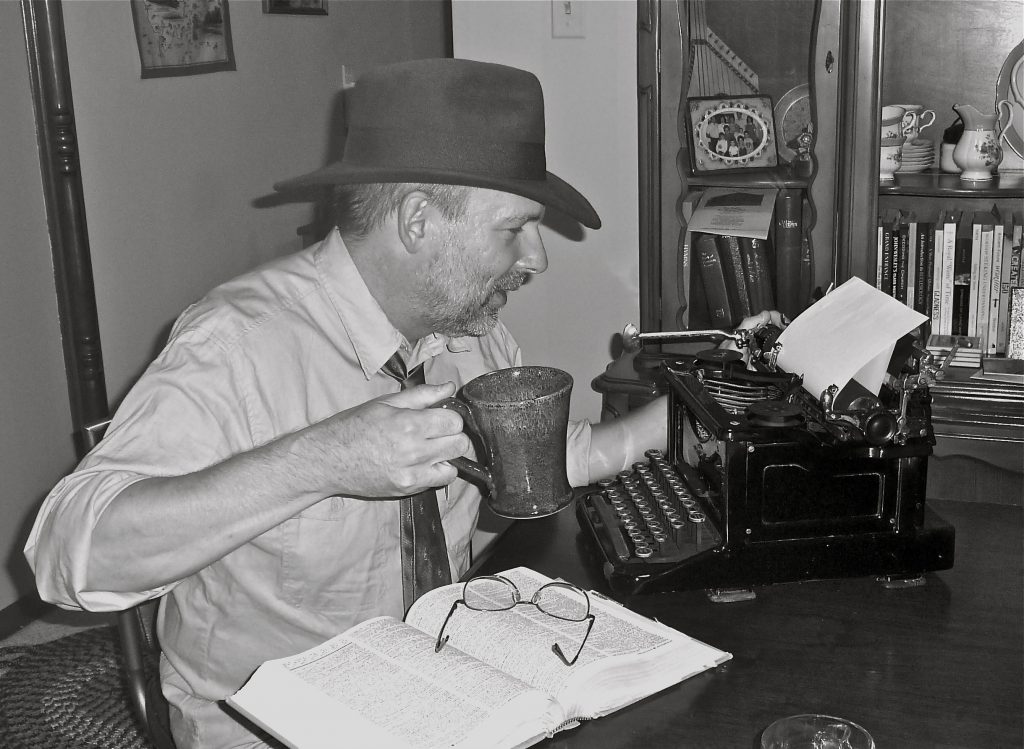

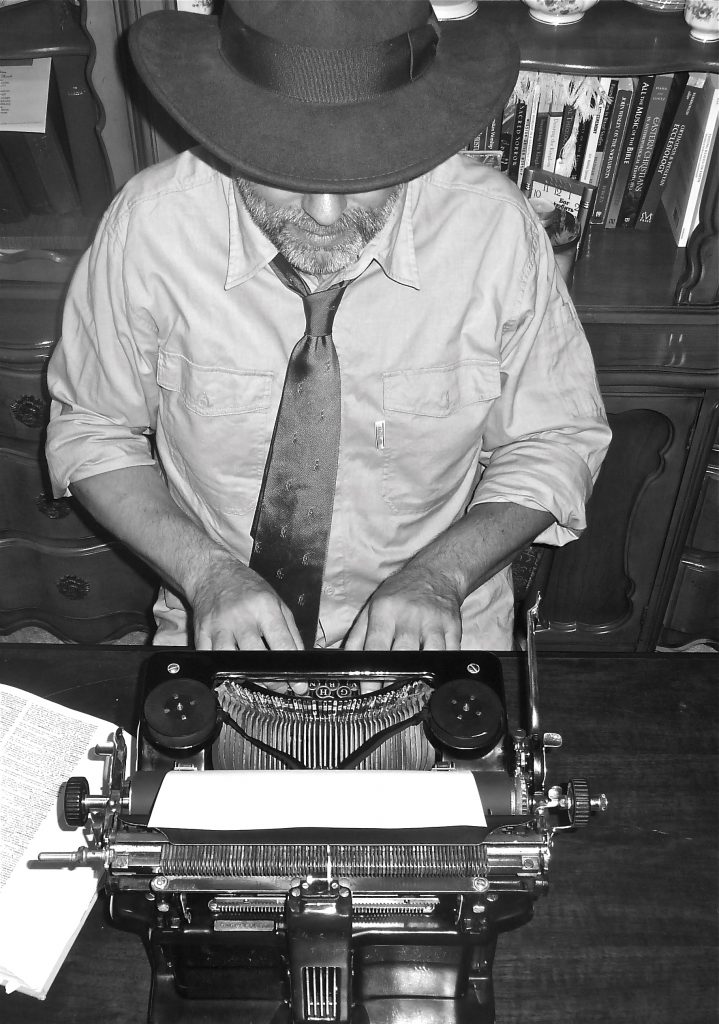

This is Aunt Ruth’s 1937 L. C. Smith typewriter that has been in our family since it was new. It’s a 79-year-old machine that, after a serious cleaning up, works as well now as it ever did. Do we have any other machines in our houses like that? Anyone? 🙂

It was like traveling into the past in more ways than one. TVs, no matter how big they got, could never match the ambience of a darkened room, the whir of celluloid and sprockets, the hot smell of the projector bulb, and the bright, flickering images on the tall tripod screen. Dad’s movies distilled the sunlight of long-past days, the green of vanished summers, the faces of relatives now old or gone.

The reel most in demand was a compilation of fifty-foot movies shot over many years, spliced together in no particular order, one section even having gotten put in upside-down and backwards, with horses galloping in reverse, consuming their dust clouds like living vacuum cleaners. Scenes of Mom and Dad’s courting blended with family baseball games—lots of swings-and-misses, and then a long, panoramic shot of a dozen guys searching for the ball in high weeds, their dark forms spread out along the horizon as if in some epic scene from a western. That one solid hit—that single moment of baseball glory—had never been filmed, so it was now claimed by every person left alive who had played that day.

I liked Julie’s answer on Facebook when a friend asked of these photos, “Does Fred really do that?” She replied, “Pose for goofy photos? Check. Use antique typewriters all the time? That, too. Sit around in a fedora and tie? Not so much.”

Dad looked like a movie star in the films, young and straight, with a full head of black hair. Mom resembled a young Audrey Hepburn.

Toward the film’s halfway point, there was a silver dot high in the sky, passing behind a transformer and power lines. This was Dad’s famous U.F.O. shot, and those old enough to know the ritual obliged him with speculation on just what it could be. The dot was so tiny it had to be pointed out to the younger kids. Always Dad nodded gravely in his chair, his gaze intent on the screen until the scene changed to the digging of the lake, which Dad had helped to survey.

“We saw more snakes than you’d believe,” Dad would say. “It was all bottomland then. I bet we saw a snake every twenty steps. Once we were all sitting on the ground in a circle, eating lunch, and a snake slithered away from right in the middle of us.”

Dad was used to being in rooms full of active little kids, so he had a habitual way of holding his cigarette like a hypodermic needle, its filter end resting on his thumb, its shaft between his first and second fingers, its hot end pointed at the ceiling, his elbow resting on the arm of his chair. If kids tumbled into him, they wouldn’t get burned.

Dad told stories about the images on the screen the same way every time, and the audience’s questions themselves followed a time-honored litany. There was very little variation of the unwritten script. That, too, was a part of the fascination of old silent eight. No music, no audio required the discipline of being quiet—not that any soundtrack could have competed with the cousins all together in one room. The audio was supplied anew by the audience each time, viewers interacting with glimpses of the past.

There were shots of dogs and of the wild fox cub Dad had found and cared for until it had grown big enough to return to the wild. Not knowing whether it was a boy or a girl, he’d called it “Jackie.” The cub was so accustomed to Dad that it would come when he called. But a domestic life is no life for a fox; the dogs would have agreed. The time came when Dad had to make Jackie go back into the woods. I’m sure it hurt them both.

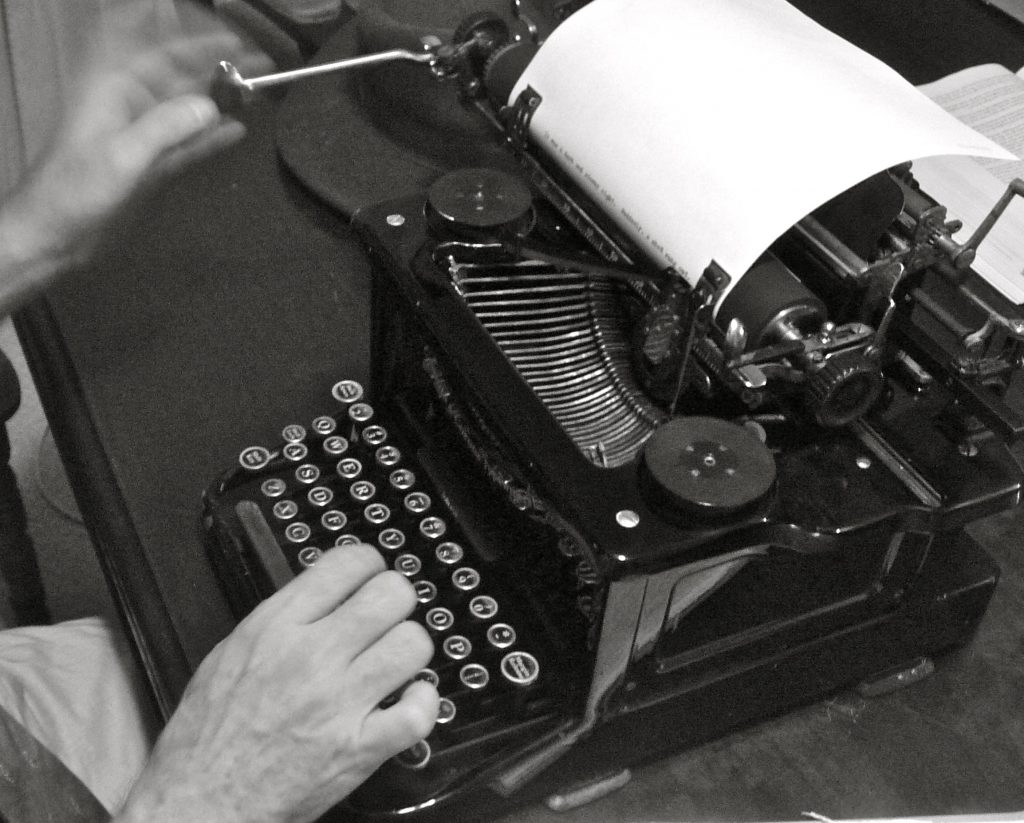

Here’s a “before” shot of Aunt Ruth’s typewriter, so you can see just how far it came in the restoration process.

Then came a full four minutes of nothing but cigarette smoke in a sunbeam at the little house, where Mom and Dad had first lived when they were married—just cigarette smoke filling the frame, curling and swirling above an ash tray. “Now wait,” Dad would always say. “Now watch. There’s a place when the smoke looks just like the Devil’s face.” A solemnity would settle over the group, and for a few minutes the summer night would take on a suggestion of chill. This was the only point on which the traditional comments varied. For sometimes Dad himself would miss the face, and would mutter, as the footage went on to other things, that somewhere in there the Devil’s face was as clear as day; and at other viewings Dad would shout “There!” in triumph, pointing. The kids in the audience would see only smoke, because they weren’t sure what they were supposed to see, or how smoke could make a picture; a few of the cousins might give a start and cry “I saw it!” and rub at the goosebumps on their arms. Some wanted to see it but didn’t. Some, perhaps, wished they hadn’t seen it. Whether Dad or anyone else saw or didn’t see the Devil in the smoke, if anyone suggested rewinding and re-watching, Dad would say, “Oh, let’s go on. It’s getting late.” And even the most curious were secretly grateful, because the drifting smoke was more than a little sinister.

Restoration complete, including a newly re-covered rubber platen (roller) from J. J. Short Associates, Inc., located a stone’s throw from Julie’s alma mater in New York.

Years ago, Dad had introduced the trick of running the film backwards in a certain part to the wild amusement of the audience. It was a scene of the cousins as kids, the oldest no more than ten, swimming in a plastic backyard pool. The audience would point, laughing at their own skinniness or braces or antics. “Is that you, Mom?” a little cousin would ask, standing up in front of the screen and reaching out a hand to touch the past—but blocking the very part of the image that held the most interest. The child would blend with the picture, the glowing colors projected on hair and skin and T-shirt back, swallowed up in the warping of light and image in a way that would have made our legendary construct of Tesla himself proud, until everyone cried “Sit down!”

The highlight came when Uncle Paul dashed across the yard in his swimsuit, the pool empty now of kids. Uncle Paul, all berry-brown, a scrawny Tarzan, dove into the pool, displacing a prodigious amount of water. At that point, my dad—and now I, the new projectionist—would switch the projector into reverse. The tidal wave would return from the lawn to the pool; Uncle Paul would fly out backwards, land on his feet, miraculously dry, and sprint away across the grass, receding into the distance. It was a delight that never grew old, when the whole group would shriek with laughter. This was what the cousins came to see year after year, bringing new spouses, new girlfriends and boyfriends, new babies. In fact, the film had its identity in this scene: the request was always for “the movie where Dad (Uncle Paul) jumps out of the pool,” as if it had been recorded that way.

It led me to wonder about the past, and still does. What actually happens does so only once, in one moment, and then is gone. But what people make of the past—what they select and believe and how they choose to describe it—that all lives on for as long as there are people to talk about it. Once it’s occurred, it belongs to us, for our re-shaping. Decades later, Uncle Paul’s jumping out of the pool was far more real to everyone than his jumping in.

What intrigued me were the images of the home and buildings I knew, appearing on the screen as their earlier selves—lines sharper, paint fresher, their stories not as long. Each time I watched it all, I was living through it, all the sweetness and the mystery and the brilliant agony of moments there and gone—life like a skyrocket.

Isn’t that interesting? As a writer, I’ve long since embraced it: we recreate the past. We live and act informed by our remembered past — some of what really was, but mostly how we remember that it was. As long as we’re alive, that remembered past is the more important one. The real one can no longer touch us if we’re here, if we’ve come through it. But the one we remember — that colors everything: who we are, what we do, the stories we tell.

Here’s your assignment, dear reader: go and look through your old photos, those in the albums, those in the shoeboxes tucked away high on the closet shelf. Or close your eyes and go back into your memories of the person you were and the world you lived in when you were small. And then tell us a story, no matter how brief. Tell it the way you remember it.