It’s officially reconfirmed: Mammoth Cave remains the best place in the world. At the end of July, we spent three nights there in the national park, in a woodland cottage. In two days, we took a total of four tours. And that’s just barely enough to grasp the enormity of the world’s longest known cave. Very little of the four tours overlap. You really are seeing different parts of this astounding subterranean world.

The longest tour, these days called the Grand Avenue Tour, is a four-mile hike underground, which takes about four hours.

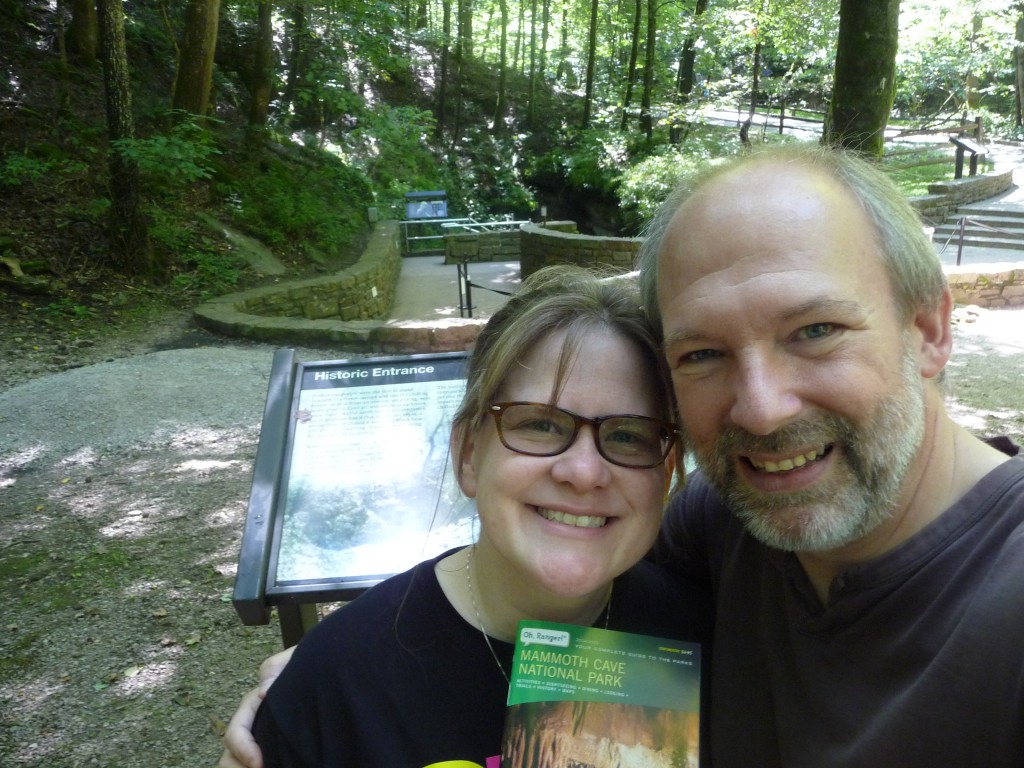

I had the great joy of getting to introduce Julie to the cave — this was her first visit to Mammoth. She was profoundly impressed. She understands it now: the Setting that lies behind all my fictional settings, the first inspiration for them all — all those underground realms and dim interiors of giant things — buildings, ships, or forests. My parents first took me to Mammoth Cave when I was about 8 or 9, and I’ve never stopped writing about it. This was my fourth visit, but in all the best ways, the experience was brand-new. I’m thankful for the insights Julie had there. There’s nothing like seeing a well-loved place through the eyes of a well-loved one seeing it for the first time. That’s what I want to write about here.

First, Julie was awed by the hugeness of Mammoth Cave. It is the colossal size for which the cave is named, not for the presence of any woolly mammoths. You walk down seemingly endless corridors the size of subway tunnels or bigger, crossing through rooms like cathedrals. If I could go there and set my own pace to look around properly and absorb the scenes, the Half-Day Tour would take more like three days.

The old Snowball Dining Room, where the Half-Day Tour used to stop and eat a boxed lunch purchased at this counter. Today the Snowball Room offers a bathroom break and a rest.

On the Violet City Lantern tour, visitors have the opportunity to see the cave in much the same way that the early guides and tourists saw it: by flickering lantern light, which allows the shadows to veil the distances and the imagination to awaken. On our Violet City tour, about every fourth person carried a lantern. Yes, I eagerly stepped up to be one of them. From Dragonfly:

“The City of Echoes itself diminished, its dark outlines fading to invisibility. Torches gleamed like fireflies along the great wall. In a matter of seconds, the well behind us looked utterly black, no different from any of the other cracks and gulfs of the deep Earth. I wondered at how frail a thing man is, at how the mere absence of a torch in such a place casts the greatest of his works into obscurity. Where was the wall piled up by the Vin Avarem; where were the houses they had built? . . . Shadows pressed around our wavering circle of light — it was unnerving not to have any idea what lay a few feet beyond.”

One famous landmark in the cave is Booth’s Amphitheater. The actor Edwin Booth — brother to the infamous John Wilkes Booth — stood on a high rock shelf there beneath a natural half-dome to deliver lines of Shakespeare to an audience below. The true story is told of Edwin Booth that, several years prior to Lincoln’s death, Edwin Booth saw a young boy fall from a train platform into the path of an oncoming train. Quick-thinking dramatist and passionate thespian that he was, Booth leaped down onto the tracks at great personal risk and pulled the boy to safety. The boy was none other than the son of President Lincoln. Edwin Booth received a letter of thanks from the President, which he carried with him in his pocket every day afterward for the rest of his life.

Anyway, at Booth’s Amphitheater, one of our guides ascended to the shelf and delivered us a soliloquy from Shakespeare (wouldn’t that be the sweetest of all jobs, other than being a full-time writer? — getting to be a Mammoth Cave guide who recites Shakespeare?!).

And that brings us to Julie’s second insight: the sciences and the humanities must come together. When they do, the experience is sublime. Here under Kentucky is a miracle of geology, a cave formed by carbonic acid dissolving the soft limestone beneath a wide, hard sandstone cap that protected it from leaks and collapses, allowing it to grow and grow in length while immemorial rivers carved it deeper and deeper. The sciences at work are fascinating and help us understand how all this happened; they allow us to discover more and more of it and teach us to preserve this gift. Combined with the human spirit, with poetry and imagination and story, Mammoth Cave becomes a miracle of experience. It inspires lifetimes of writing. It makes children of us all. It allows slaves to become masters in its embrace.

The first modern guides were black slaves such as the true father of Mammoth Cave exploration, Stephen Bishop. Though he was owned by another man, in the depths of the Earth, Stephen called the shots. He was the one who knew the way in and the way out. The wealthiest aristocrats from around the world came to see Mammoth Cave and asked for Stephen to guide them; they would wait for days until he was available. His life was short but wondrous. I know of no one who owned his surroundings more or took a firmer hold of life with both hands. Stephen taught himself letters by offering to write rich tourists’ names on the cave ceiling with the smoke from his candle. He is buried high on the wooded hillside a stone’s throw from the historic entrance of the cave he loved, and that is something right about the world. I stood as close to his grave marker as the fence would permit and stretched out my hand, thanking him for crossing that Bottomless Pit on a rickety ladder, the water crashing on unseen rocks far below . . . for making his maps and wriggling into forsaken holes, for raising his smoky lamps like the Phial of Galadriel in dark places when all other lights had gone out — for knowing there were wonders to find. At the end of his life, Stephen was as free a man on the surface as he was below.

Mammoth Cave is full of human stories. Millennia ago, the ancient ones came with their burning reeds, chipping gypsum from the walls, questing deep, using the cave in ways that we can only guess at. Some became mummies, interred in the Earth’s grandest tomb. One lay undiscovered until modern times, scant feet to the side of a well-trod tour path. Then came the miners of saltpeter with their picks, shovels, and wooden bins. They provided our country’s gunpowder for the War of 1812. And then there were the pale walking dead, the doomed tuberculosis patients living in canvas shelters, in huts of stone far from the light, seeking a cure in the cave’s even climate; they sat, they wandered, they choked on the greasy smoke of their cook-fires and lights, they fled and died. There came the showmen, the entrepreneurs, the guides, the wondering public from near and far. And then Mammoth Cave took its place as a national park, the great cave of the eastern U.S., protected and open to us all.

My wife confessed that she’d always viewed caves as side-trips — something to do with a free hour near the main attraction you’d traveled to see, especially if the weather was rainy. She’d seen the cave experience as the descent of a stairway to look at some lovely formations, then back to the surface. But Mammoth Cave turns that perception on its ear. It blows it a-WAY.

This was Julie’s observation that struck the deepest chord with me: Mammoth Cave is a journey.

According to popular legend, this Natural Entrance of Mammoth Cave was discovered by a Kentucky boy chasing a bear he was trying to shoot.

You hike down a trail through a steamy, muggy forest. (It was in the glorious mid-nineties while we were there!) All at once, you feel it: the air has changed. There is an edge, a breath like winter. Natural air-conditioning — the exhalation of the Deep Earth. It has come to you and opened its maw.

The way leads you down. Forest green gives way to rough, gray-black rock, older than the trees, older than anything that now lives on the Earth, even those giant clams in their watery Deep. Water drips and echoes. The cave’s breath is cold, enveloping you. I am changeless, it whispers. Down here in me, life means nothing. Time means nothing. There is only darkness and vast, vast space. You may see a little of it, as long as your light and your short, short breath last. If you lose your way, I do not care. It is not the darkness that will destroy your mind; it is the silence.

But you are with a ranger, an experienced guide — with two, in fact, for a second always comes at the rear, closing gates, turning off lights, herding the stragglers. Between these two, you walk. You look and listen. You think and feel. You hear stories and facts; but most of all, you see what the Earth shows you. You see high vaults, the mystery of side passages winding away. You see cracks and uncounted tons of jumbled rock, slabs like ballroom floors fallen from the ceiling in eons past. You climb mountains. You cross bridges where water roars. You squeeze through Fat Man’s Misery and creep beneath Tall Man’s Agony. You rest, you drink water, and you walk again.

When you come out — far away, at a different entrance, miles from where you went in — you are not the same person that you were, not quite.

“Easy the descent by Avernus;

Night and day, black Death’s door is open wide;

But to retrace your steps and emerge to the fresh air above,

This is an undertaking, this is a labour.”

— the Cumaean Sibyl, speaking to Aeneas in Virgil’s Aeneid

Is this not at the heart of story? — a journey that leaves us changed?

This is Mammoth Cave. We commend it to you.

P.S. — H. P. Lovecraft wrote a story set in Mammoth Cave. Did you know that? It’s pretty cool!