I appreciate Hallowe’en more with each passing year. There are good reasons the holiday is so fiercely and fondly embraced in the U.S.: mainly, it’s a celebration for all ages. For the very young, it’s about masquerade and pretend; it’s about games, great treasure-hoards of candy, and spooky thrills. But it’s as we move onward from childhood that Hallowe’en sets its claws deeper into us. Its influence is inextricably tied to the season. Autumn is the time of memory. Spring is resurrection, excitement, commingled hope and sadness, and the ache of new growth; summer is all about living. Winter is grim survival, head down, teeth set against the wind, prayers for warmth. But autumn . . . the time of rarefied beauty, when all the trees and hills are glorious and tragic, when the wind and the thin sun sing their arias of death, and darkness lurks a half-glance away . . . that’s the time when we stand still, catching our breath and counting it as it slows, knowing those inhalations are finite, that the harvest basket of them is not nearly as full as it was when we started out.

We stand beneath the crimson leaves, and we are rightly awed. Life is a gift, and we are given an abundance of moments infinitely valuable. Autumn helps us recognize their brevity and their beauty.

It’s striking how the progression of Hallowe’en/Thanksgiving runs before Advent/Christmas. The first set looks ahead to the second. Hallowe’en, like Advent, gives us a world in darkness, a world of horrors and mortality, a people huddling, haunted, and hunted. With Thanksgiving/Christmas, light and help arrive. Feasting can begin. Christmas is all about joy: looking back with fondness, looking around in glad fulness, looking forward in sure hope. But Hallowe’en . . . Hallowe’en allows us to hear the dark chords in the music. It’s the time at which we can gaze into the fire and glimpse that from which we are saved. Theologically, it’s a holiday of marvelous richness. Nostalgically . . .

See, that’s where Hallowe’en bridges the gap between children and adults. When we grow too tall for trick-or-treating, it occurs to us that Hallowe’en is mostly about what we remember. It’s not just the times we recall — the family and friends (though those are certainly a part of it); rather, we remember the things we imagined . . . the things we did and how we felt while doing them. We remember how Story intersected our lives. Hallowe’en is a deliciously personal holiday, because generally speaking, we begin to enjoy it most as we begin to leave our comfort zones. Am I right? I’m betting most of your best Hallowe’en memories involve adventures — and people you chose to be with. Those might have been family members, but not necessarily so. Hallowe’en is the holiday of Not-Necessarily-So. I’ll wager that your memories involve borders and danger, or the possibility of danger. They’re memories from the edge of light, when you began to understand that you could and would get hurt out there, but you went anyway, out to where twigs snapped and howls echoed over the hills. You went because it was worth it. And it still is. Hallowe’en is the holiday of beginning to grow up. It’s when hobbits turn fifty. And yet . . . and yet . . . it’s the holiday of never growing up, not in the ways that lead to loss.

So here are a few of my best Hallowe’en memories from my years in Japan.

I first went over in October of 1988, and that is the year that I was first writing real, grownup stories — not imitations of movies and my favorite books anymore, but actual stories. That summer (just after college, and on the threshold of Japan), I wrote two long short stories, “Iowa Mud” (accepted by the delightful Midnight Zoo, but never published because the magazine folded before my story appeared) and, even before that one, “Maybe Tonight.”

Now, “Maybe Tonight” has never been published, and rightly so: I’m sure it has plenty of flaws. But what it really is is a performance piece. Read aloud under the right conditions, it works — as I found out that first Hallowe’en night in Japan.

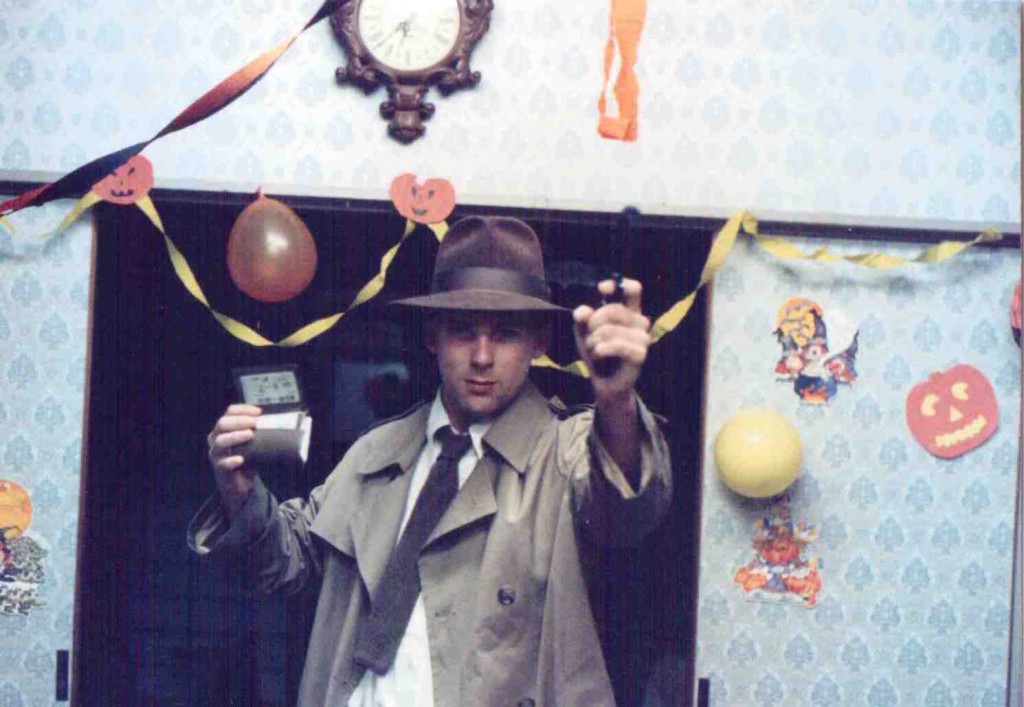

That autumn, I was in our Orientation for the volunteer mission program that took me to Japan. I lived with a Japanese Christian family in Tokyo and studied Japanese language daily at the Tokyo Lutheran Center. For a Hallowe’en festivity, some of us gathered in the tiny apartment where two of my fellow volunteers lived — in the Takenotsuka neighborhood, if I remember right. I don’t recall exactly who was there — mostly girls, and two of our students, a teenage boy and a young working lady who arrived late. Brenda was there, and I think Marit and Chris . . . who else? The group included Nancy, one of our directors, 27-ish in age to our typical 22-23-ish. Young people. Goodness, how young! I was dressed as Ed Grimley, and I looked, sounded, and acted disturbingly like him. My co-worker Dave (not the cat of the photo above) was wearing an enormous purple Afro wig. That’s all I remember about the costumes.

Anyway, there were about a half-dozen of us, and the main event of the evening was that I’d been asked to read “Maybe Tonight” aloud. Just one story?, you ask. Yes, well, it was upwards of 10,000 words — plenty long enough for an evening’s entertainment, after the talking and eating — kind of like watching an hour-long holiday special. We sat in a circle on the floor, close together because the place was so small. I think the only light was from a candle or two. Dark shadows filled the corners and crowded around. The near-endless city of Tokyo rumbled and rattled outside.

“Maybe Tonight” is the story in which Henry Logan made his debut — the mortician who went on to become Uncle Henry in Dragonfly. In “Maybe Tonight,” he’s a little crazier and with a wicked streak. I won’t give away the ending, but the story is about a young man named Lester who has driven a long way to meet Henry Logan and interview him for an article he’s writing. Lester is extremely nervous by nature, and he arrives in the small Midwestern town at night, during a thunderstorm. A worsening flood strands him there. Through details he observes, through things he hears, little by little, Lester realizes that the dead in this colorful little borough don’t stay dead; further, he learns that he’s agreed to spend the night in Logan’s funeral home, where there are a couple recently-arrived corpses who are most likely not going to remain inanimate. The few townspeople Lester meets react differently to what is happening. The mystery deepens, and the tension mounts. It’s a silly story in some ways — playful, darkly humorous. But it amounted to one of the two best reading-a-story-aloud experiences I’ve ever had. It was a LOT of words to sit through . . . but the audience never grew restless. They behaved in all the ways a performer hopes for, huddling closer, yelping at the scares, laughing at the jokes . . . The best moment was when, because the story was long, I offered to skip a bit, and Nancy yelled, “Just READ!”

Yeah, that was fun. It was my first grownup story, a Hallowe’en performance I’ve never forgotten, with some great friends, all settling into the wild adventure of living in a new land, around the world from home. Maybe I should dust off “Maybe Tonight” and do something more with it.

I think it was the same year as the Ness photo above, 1989 — my first Hallowe’en in Niigata — that I chose to decorate my apartment as a cave. I’ve never been so ambitious again on any Hallowe’en since. For that, I got a whole bunch of construction paper of various colors and cut out literally hundreds of stalactites and stalagmites. These I taped to the ceilings and the bottoms of walls all through my apartment on Matsunami-cho. I think it took a night and a day (like the destruction of Atlantis). And what’s more, I acquired a roll of green, transparent plastic ribbon to serve as “drips” — streams of water trickling down from the stalactites — not from all of them, but from enough that walking through my apartment was truly inconvenient. I made a lot of tacos and invited my evening English conversation class over to eat and enjoy Hallowe’en. Although I explained the holiday’s origins, there are probably still some surviving members of that class who believe that All Hallows Eve is when Americans decorate their homes like caves and eat Mexican food.

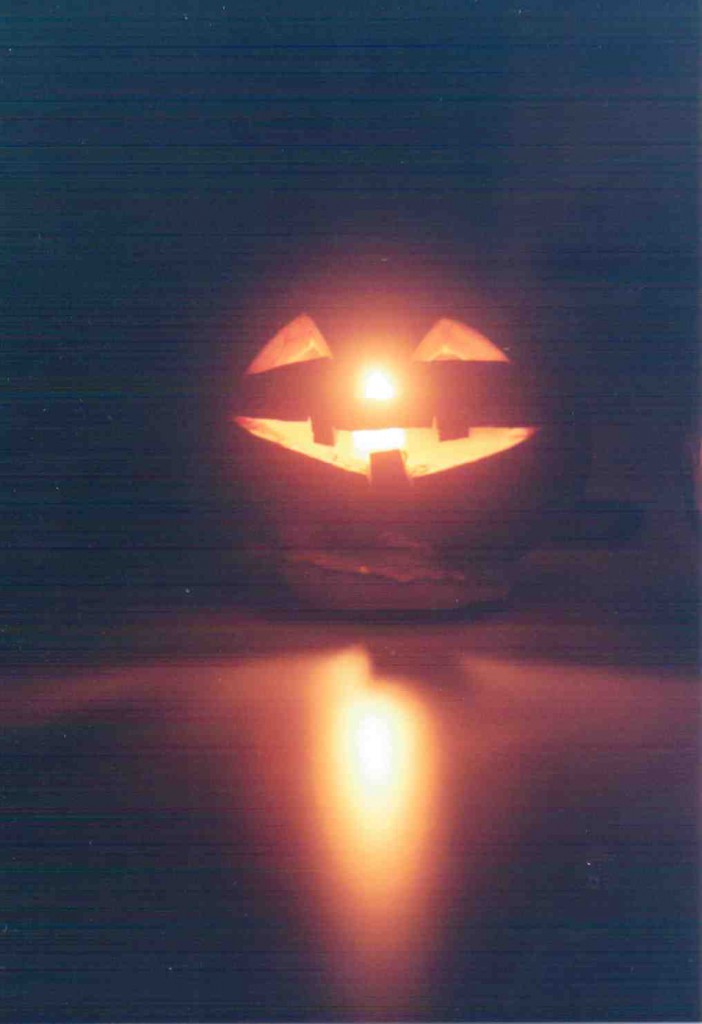

I quickly discovered that, particularly in the earlier years of my time in Japan, big orange pumpkins were not available. As time passed, they started appearing in small numbers, but they were horrendously expensive. But if I wanted jack-o’-lanterns, I had to learn to carve the little green kind. These are slightly larger than a grapefruit — no bigger than a cantaloupe — and with tough, hard shells. And there were no special pumpkin-carving tools in Japan, because jack-o’-lanterns weren’t a thing. I was using large, cumbersome kitchen knives. My Japanese friends couldn’t stand to watch . . . but I never did get injured from pumpkin-carving (by grace).

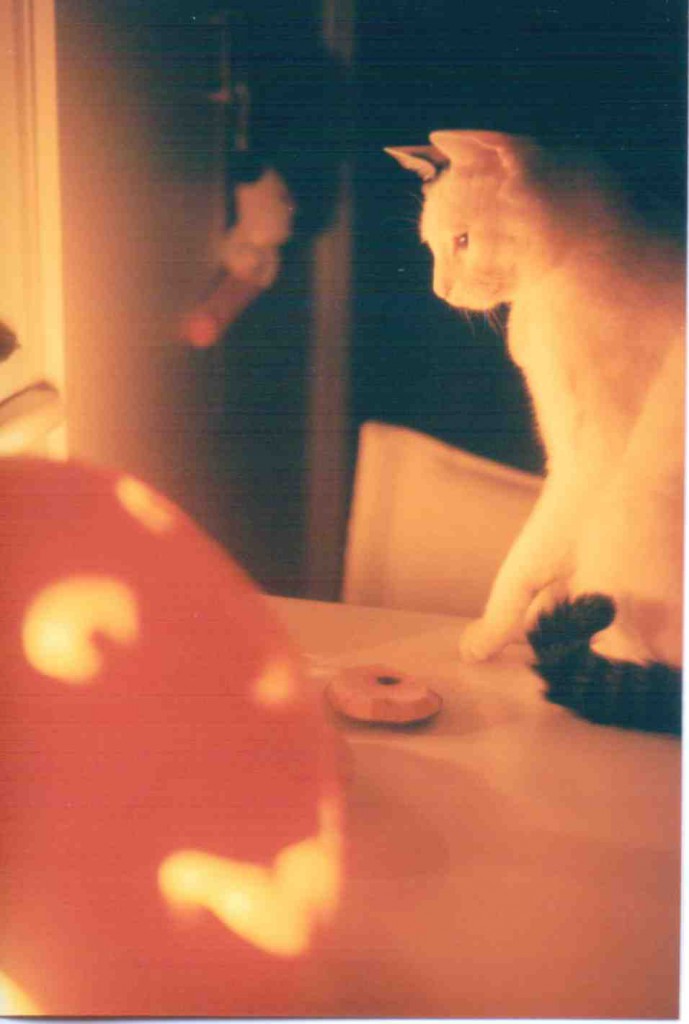

1992. I always loved taking pictures of them on that kitchen table because of the eerie reflected light.

These pumpkins in Japan, of course, are for eating. Shopkeepers would wonder why I was buying so many at once, and my friends would shudder about equally at the prospect of wasting good food and at the prospect of my producing a huge kettleful of pumpkin innards that needed cooking or preserving somehow. I remember making a vat of stringy, seedy, pumpkin miso soup one year, and my co-worker Scott tactfully remarking, “Mmm. This tastes . . . healthy!” As my friends got used to my annual custom, they started blending my pumpkin meat into better soups (hard to beat a rich, pumpkin-cream soup) or baked desserts. We tried roasting the seeds, but the seeds of little green pumpkins don’t work as well for that. The green pumpkins themselves are much more flavorful than the big orange kind. In Japan, they’re usually eaten shell and all.

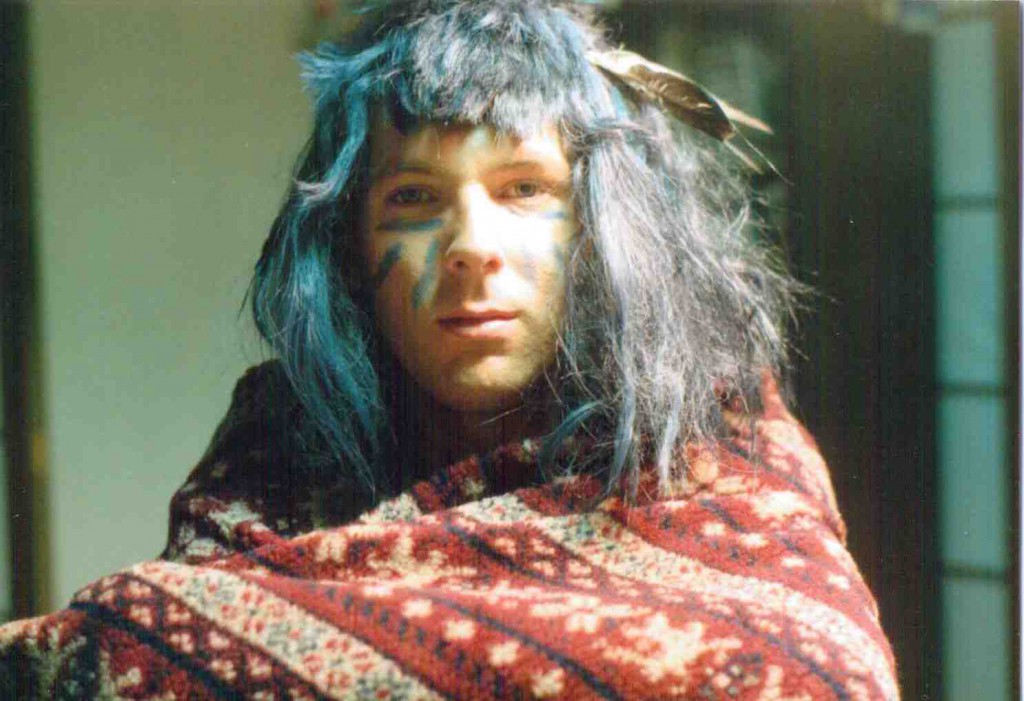

Some sort of native, 1991. Actually, this was inspired by DANCES WITH WOLVES, and I decided my Indian name was “Under-the-Ground.” Note the silhouette of a shoji window in the background.

It’s amusing to remember how I set out a jack-o’-lantern on my second-floor balcony at Mezon Matsunami, facing the busy street of Matsunami-cho. It was the only jack-o’-lantern, I’ll wager, in the entire city, flickering bravely in the dark October night. Passing pedestrians and drivers must have wondered, “What is that?”

It was always fun to seek out pumpkins each fall. I’d buy them mostly from farm grandmothers who had vegetable stalls in the market street. I’d deliberate over the pumpkins, picking out the sizes and shapes I liked, and the ladies would assure me, “They’re really delicious! These are sweet!”

“Why ‘Happy Hallowe’en’?” my Japanese pastor would ask me. “Why is it happy?” I’d give him my rationale about how applicable it was to Christian truth. I don’t know if he was entirely convinced. But I do know that the church at Shirone, at first skeptical of my idea for a Hallowe’en party, eventually embraced it so enthusiastically that they continued holding it every year long after I was gone, and it turned into a major church event, complete with a costume contest, games, and a deliberate Christian message and invitation to visitors to join the church members for any of their gatherings. I wonder if the congregation at Shirone still does that.

Gandalf, October 31, 2002, Niigata: a friend and I took this picture in the parking lot of a restaurant, and we realized that a great many customers from the dining room were pressed up against the plate glass windows, watching us — and when I glanced up and saw them, they all applauded!

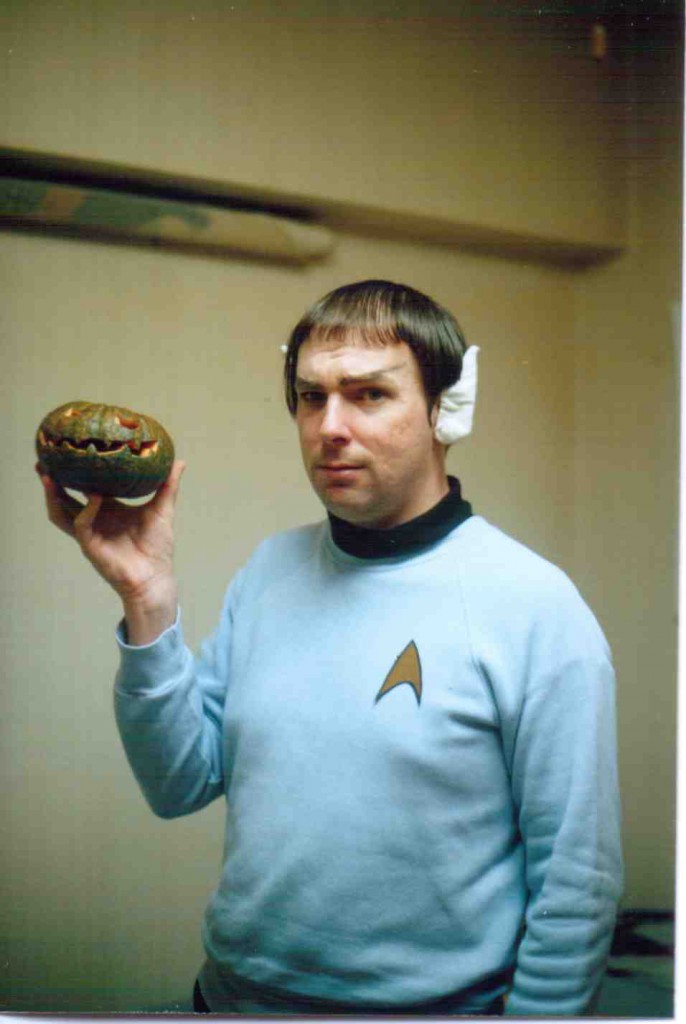

During my year in Shirone, I lived in a very rickety, cold, second-floor apartment. Through the warmer months, I shared it with many spiders and earwigs, and even little frogs from the rice fields would climb up as high as my balcony. I’d find them clinging to my windows and frosted-glass door. Anyway, most of the apartments in that complex were occupied by Brazilians who had come to work at the local candy-and-cookie factory. It was a cheerful place to live. Parties went on quite often, with everyone’s doors wide open, the tantalizing aromas of cooking wafting everywhere, and people freely mingling, drifting from one apartment to another. Now, I had dressed as Mr. Spock that Hallowe’en . . .

I knew I was going to pass about fifty jovial Brazilians on my way to church for the Hallowe’en party. The volunteer before me had left a pocket-sized Portuguese-English dictionary in the apartment, and I was trying to figure out how to say “Hallowe’en” — or, failing that, at least “party.” But I needn’t have worried. No sooner had I stepped out of my doorway than I was exuberantly greeted with “Heeeyy! Mr. Spock! All right! Good, good!” and given many thumbs-ups. I invited people to come along with me to the church party, but they were having too much fun at the party that was our neighborhood. They were good neighbors, and we always got along well. After Mr. Spock passed them on his away-team of one, we were on even friendlier terms.

Those are the memories of Hallowe’en in Japan. No one really knew what it was about, but most were glad to humor me, and everyone likes a good masquerade.

The Japanese could relate to Hallowe’en because it’s so much like their festival of Obon, which happens in mid-August. That’s the time when the spirits of the dead return to Earth, and when people tell creepy stories. I’ve heard the reasoning that the hottest nights of summer are the best time for ghostly stories, because the chill of fear cools people down.

Could this be the Great Pumpkin that Linus waits for? Maybe he found a very sincere pumpkin patch in Niigata in 1995.

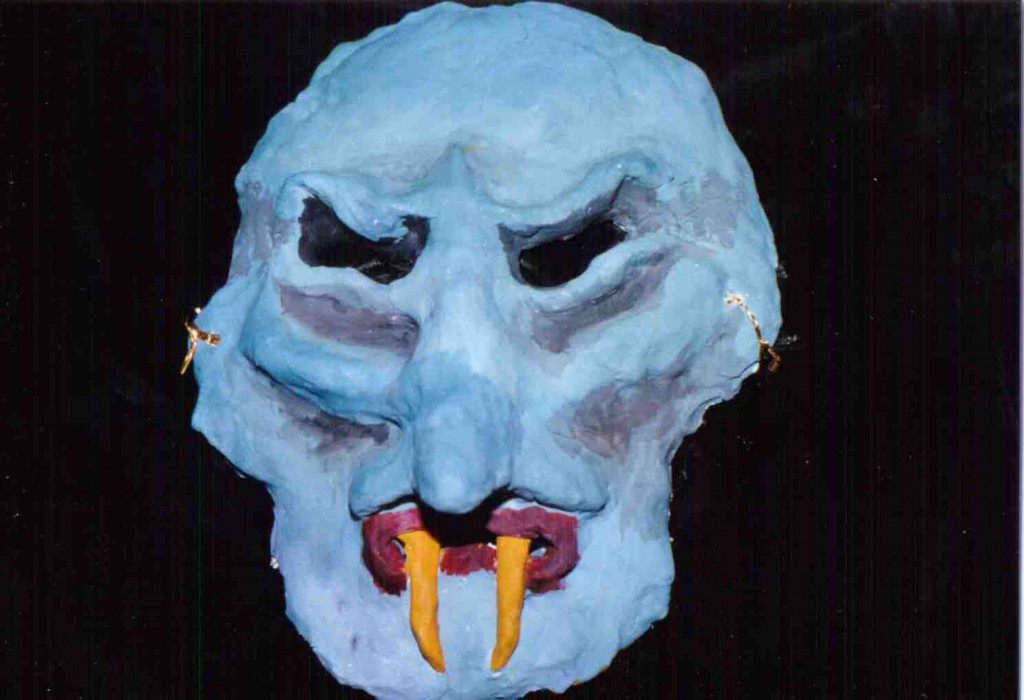

I haven’t shown you all my costumes from the Japan years. The scarecrow is missing . . . the dark-seeing Hurlim from The Fires of the Deep . . . and the nightmarish bird-creature, which is best left undepicted. The hour grows late, but here is one more:

For the last words, I’d like to quote from “Boo,” by Richard Laymon, the best Hallowe’en story I know of:

“And I’ll always remember trotting up those stairs and stepping onto the dark porch and walking up to the front door. Even while it was happening, I knew I would never forget it. It was just one of those moments when you think, It doesn’t get any better than this. / I was out there in the windy, wonderful October night with cute and spunky little Peggy Pan, with my best buddy Jimmy, and with Donna. / . . . / Now she was about to ring the doorbell of the creepiest house I’d ever seen. I wanted to run away screaming myself. I wanted to yell with joy. I wanted to hug Donna and never let her go. And also I sort of felt like crying. / Crying because it was all so terrifying and glorious and beautiful — and because I knew it wouldn’t last. / All the very best times are like that. They hurt because you know they’ll be left behind. / But I guess that’s partly what makes them special, too.”

Happy Hallowe’en!