“It was getting very late when we came to a certain house that was not at all like the others on its block.”

–from “Boo,” by Richard Laymon

October is in the chair, as Neil Gaiman might say — and has said! — check out his story “October Is In the Chair” in his collection Fragile Things. But seriously, it’s October now. Much as I love the summer, much as I believe the hot months are the real incubator of the imagination, and that they are the closest months we get to Paradise in this life . . . I have to admit that October is the single most focused imaginative month. After we’ve charged far afield and frolicked and absorbed as much sun as we could through the warm months, it’s sober October that sits us down before the fire and makes us gaze into the darkness of things. We catch our breath, and we shiver. We remember how good it is to be scared by a scary tale — so much better than being scared in real life! In stories, we just can’t resist seeking what’s out there — what’s down there. What might be coming, even now.

I have fond memories of growing up with tales of weirdness and fear. First, Andersen’s fairy tales: whenever I was sick as a kid, lying on the blue velvet sofa, shivering and sweating and unable to hold liquids down, Mom would get out the little blue hardback collection of Andersen and read to me. Strange and scary things happened in those stories. There were witches and magic, dogs with eyes as big as saucers, and my experience of them came with the mingling of physical discomfort, delirium, and the wonderful glow of love, care, security, and relief. My mom was there, taking my temperature and bringing me Seven-Up. And that, I believe, is fundamental to my perspective on horror. If I didn’t have a core belief that things will be all right, I’d have no reason to enjoy horror.

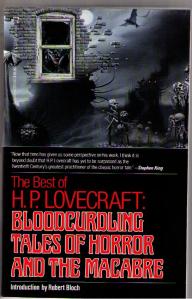

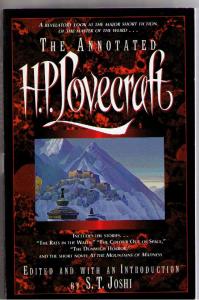

Then there’s H.P. Lovecraft. I think I’ve mentioned before how I used to see the covers of his books on the racks at our family bookstore, and they looked like the perfect books to me as a nine- or ten-year-old boy: hideous monsters, tentacles, crumbling stonework, etc. Oh, how I wish I had an image here of the very first cover that drew me to Lovecraft! I’m pretty sure it was a collection called The Dunwich Horror and Others. At any rate, the edition you read doesn’t matter too much, as long as it’s Lovecraft, and as long as you read enough stories to get a feel for him. I particularly recommend The Annotated H.P. Lovecraft, edited and with an introduction by S.T. Joshi. There’s also a More Annotated H.P. Lovecraft, annotated by S.T. Joshi and Peter Cannon. Although I’m talking October books here, my childhood recollections of Lovecraft are of the dusty back room of our bookstore, reading and drinking Pepsi with my knees propped up against the edge of the battered desk . . . and of reading him outdoors at

Then there’s H.P. Lovecraft. I think I’ve mentioned before how I used to see the covers of his books on the racks at our family bookstore, and they looked like the perfect books to me as a nine- or ten-year-old boy: hideous monsters, tentacles, crumbling stonework, etc. Oh, how I wish I had an image here of the very first cover that drew me to Lovecraft! I’m pretty sure it was a collection called The Dunwich Horror and Others. At any rate, the edition you read doesn’t matter too much, as long as it’s Lovecraft, and as long as you read enough stories to get a feel for him. I particularly recommend The Annotated H.P. Lovecraft, edited and with an introduction by S.T. Joshi. There’s also a More Annotated H.P. Lovecraft, annotated by S.T. Joshi and Peter Cannon. Although I’m talking October books here, my childhood recollections of Lovecraft are of the dusty back room of our bookstore, reading and drinking Pepsi with my knees propped up against the edge of the battered desk . . . and of reading him outdoors at  home on hot, hot summer days — heat and light all around me, heat waves shimmering in the fields, leaves whispering in the breeze — and in the pages, coldness and subterranean darkness, moldering crypts, secret rooms, sagging gambrel roofs in ancient New England towns. . . .

home on hot, hot summer days — heat and light all around me, heat waves shimmering in the fields, leaves whispering in the breeze — and in the pages, coldness and subterranean darkness, moldering crypts, secret rooms, sagging gambrel roofs in ancient New England towns. . . .

Lovecraft is one writer I enjoyed as a kid and kept right on reading as I grew up. Back in about 1995, I lived and taught in the town of Shirone, but I also had a couple classes once a week in Sanjo. To get there, I took a bus to a tiny train station in the middle of nowhere (a town/station called Yashiroda), where sometimes I had to wait well over an hour for a train to come along. I would sit there at the station reading H.P. Lovecraft — outdoors in the summer; in the winter, cozied up to the kerosene stove inside.

In gradeschool we used to have Book Fairs in the “All-Purpose Room” — a big gray chamber at the heart of the building where lunch tables and seats folded down out of the walls, then retracted again when it was time for an all-school assembly, band practice, a play, a film, or p.e. class. Such Fairs were a delight: there were tables stacked with books, and you could browse among them and buy them for ridiculously low prices like five cents or ten cents. (At least that’s how I remember it now — any North School kids out there want to correct me?) It was at one such Book Fair that I bought a morbidly grim volume called The Creature Reader. And one of the stories in it was “Wendigo’s Child,” by Thomas Monteleone. It was about a boy in Arizona who rides his bicycle to a nearby archaeological dig, hoping to find cool artifacts, and he finds a little, leathery, wizened mummy that seems half human baby and half bird. Ill-advisedly, he takes the thing home and hides it in his basement, finding out along the way from a native American friend (to whom he doesn’t show the mummy) that such creatures were guardians of the burial grounds. Yes — what you’re imagining — that’s what happens in the story. The book gave me nightmares for months afterward. I loved it!

There was also a story in that book called “Godosh” [the author escapes me], about a sleeping giant inside a mountain who wakes up and wreaks a terrible vengeance when heartless land developers come to bulldoze the forest. Very satisfying to a pre-teen nature lover’s sensibilities!

I don’t know what ever happened to my copy of that book. I’m one who takes very good care of books, and I rarely lose track of ones I like. But the fate of that one is a true mystery. It vanished without a trace at some point.

There was a book called Shudders on the shelf in my bedroom for years and years. (When I visited my Cousin Phil’s parents back in 2006, I noticed a copy also shelved with his old books, which didn’t surprise me. We tend to gravitate toward many of the same books, even if they’re really obscure.) I honestly don’t know whether it’s a good collection or not, because I never got past the first story: “Sweets to the Sweet,” by a young Robert Bloch. That story scared me so badly as a kid that I stopped reading, put the book back into the bookcase, and didn’t touch it for what I think was a couple years. When I opened it again and read the Bloch story, it scared me again and I put it back on the shelf. I’d say there’s a fairly good chance that if I found the book again today, I still wouldn’t make it past the Bloch story.

As a teenager, I got into much of the earlier work of Stephen King. I devoured The Shining, I loved his short stories in Night Shift, and ‘Salem’s Lot is still one of my favorites of his — and one of the best vampire books around. But my favorite Stephen King is the novel It. (The novel, I stress: don’t even bring up the visual dramatization of it!) I read It at a major transition time in my life: I started it in the early summer of 1988, my final year in the States; I finished it in Tokyo in the winter of 1988-9. So my memories of it are bound up with both Illinois and Japan, and that time of moving to a new phase of life. It — to my thinking, this is the very best of Stephen King. All the pulse-racing, skin-crawling horror is there, but it’s tempered by an achingly beautiful nostalgia for childhood in a vanished era and a portrait of lifelong friendships — friends who will stick with each other though their lives hang in the balance. It’s a wonderful book.

During one of my first few summers in Japan, I found my way to the stories of Algernon Blackwood. In those years of my early twenties — a searching, angry, passionate, lonely, joyous, discovering time — I used to sit astride the seat of my parked bicycle on some forest trail near the sea, and in the green glow of filtered light, I’d read books. That’s where I read Blackwood’s “The Willows,” one of the scariest stories of all time. It was at around this time — 1990 or 1991 — that I had a very close brush with publication. A now-defunct small-press magazine titled Midnight Zoo expressed strong interest in my story “Iowa Mud,” but asked for revisions. I immediately subscribed to the magazine, revised the story, and sent it back. As I recall, they liked it still more, but wanted more revisions. So I obliged them. I loved reading the magazine — it was well put together, and the stories were right up my alley. They accepted the story, but before it saw print, they got into financial problems, as small-press magazines almost inevitably do. They asked if they could pay me in contributor copies instead of money, and I said sure. Then they ceased publication and disappeared altogether, and I never heard from them again. The story never made it into print. (Which may be a good thing.) [Oh — the point of telling about this near-publication experience {NPE} is that I sat around in that same pine forest revising “Iowa Mud,” so my memories of that time are all interwoven — my story, Blackwood, and Ambrose Bierce.]

During one of my first few summers in Japan, I found my way to the stories of Algernon Blackwood. In those years of my early twenties — a searching, angry, passionate, lonely, joyous, discovering time — I used to sit astride the seat of my parked bicycle on some forest trail near the sea, and in the green glow of filtered light, I’d read books. That’s where I read Blackwood’s “The Willows,” one of the scariest stories of all time. It was at around this time — 1990 or 1991 — that I had a very close brush with publication. A now-defunct small-press magazine titled Midnight Zoo expressed strong interest in my story “Iowa Mud,” but asked for revisions. I immediately subscribed to the magazine, revised the story, and sent it back. As I recall, they liked it still more, but wanted more revisions. So I obliged them. I loved reading the magazine — it was well put together, and the stories were right up my alley. They accepted the story, but before it saw print, they got into financial problems, as small-press magazines almost inevitably do. They asked if they could pay me in contributor copies instead of money, and I said sure. Then they ceased publication and disappeared altogether, and I never heard from them again. The story never made it into print. (Which may be a good thing.) [Oh — the point of telling about this near-publication experience {NPE} is that I sat around in that same pine forest revising “Iowa Mud,” so my memories of that time are all interwoven — my story, Blackwood, and Ambrose Bierce.]

About Blackwood: in the same collection, he has a story called “The Other Wing” which I always thought completely surpasses any notion of “genre.” It ought to be anthologized in college freshman literature survey textbooks, along with Lovecraft’s “The Strange High House in the Mist.”

The years have gone by, and I’ve always been on the lookout for good, scary tales. I know some people just don’t “get” horror, but given the choice between any two stories, I’ll almost always take the frightening one. (Like I said a few posts back: our oldest fully-English piece of literature is the story of a hero battling monsters — it’s in our blood.)

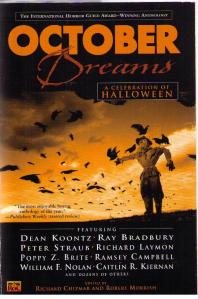

My first novel Dragonfly was/is an ode to Hallowe’en. And speaking of that holiday: THE BOOK to read in this season (while you’re taking breaks from Dragonfly) is an anthology entitled October Dreams, edited by Richard Chizmar and Robert Morrish. What makes this one so wonderful is that it isn’t just a compilation of great Hallowe’en stories by a whole host of writers, some extremely famous, some virtually unknown — but it also includes, between the stories, mini-essays by many of the writers on actual memories of Hallowe’ens in their lives. If you read it, you may even decide you like the essays best of all. In fact, I’d love to see a whole book dedicated to that. Someone should solicit Hallowe’en memories from about fifty speculative fiction writers, ranging from the bestsellers to those in the small press — wouldn’t that be excellent? Anyway, in that book is my favorite short Hallowe’en story ever: “Boo,” by Richard Laymon. I won’t spoil it by giving away particulars, but I will say that this story captures pretty much everything I love about Hallowe’en. It’s beautiful and nostalgic; in places it makes you laugh out loud — partly at what’s happening, and partly at your own memories it evokes — it makes you ache with longing, not only for the Hallowe’ens of your youth, but for childhood itself — and, like any proper All Hallows tale, it packs a deeply disturbing wallop. “Boo,” by Richard Laymon — I dare you to find better! (And if you find better, please please pleeeease tell us about it here!)

My first novel Dragonfly was/is an ode to Hallowe’en. And speaking of that holiday: THE BOOK to read in this season (while you’re taking breaks from Dragonfly) is an anthology entitled October Dreams, edited by Richard Chizmar and Robert Morrish. What makes this one so wonderful is that it isn’t just a compilation of great Hallowe’en stories by a whole host of writers, some extremely famous, some virtually unknown — but it also includes, between the stories, mini-essays by many of the writers on actual memories of Hallowe’ens in their lives. If you read it, you may even decide you like the essays best of all. In fact, I’d love to see a whole book dedicated to that. Someone should solicit Hallowe’en memories from about fifty speculative fiction writers, ranging from the bestsellers to those in the small press — wouldn’t that be excellent? Anyway, in that book is my favorite short Hallowe’en story ever: “Boo,” by Richard Laymon. I won’t spoil it by giving away particulars, but I will say that this story captures pretty much everything I love about Hallowe’en. It’s beautiful and nostalgic; in places it makes you laugh out loud — partly at what’s happening, and partly at your own memories it evokes — it makes you ache with longing, not only for the Hallowe’ens of your youth, but for childhood itself — and, like any proper All Hallows tale, it packs a deeply disturbing wallop. “Boo,” by Richard Laymon — I dare you to find better! (And if you find better, please please pleeeease tell us about it here!)

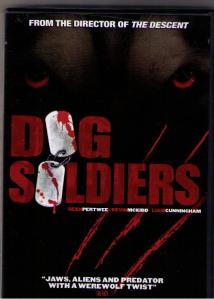

Finally, two movies I’ve seen recently, which represent a tip of the hat to those two mighty pillars of the horror genre, the vampire and the werewolf. . . . Several friends had been recommending to me the film Dog Soldiers (2001). It is a genuinely creepy and entertaining story, and it’s the sort that I think I may like better on subsequent viewings. (To be 100% honest, after the way so many trusted friends raved about it, I was a tiny bit disappointed on my first watching; it’s a good film, but it had a lot of hype to live up to. But I liked it enough that I’m talking about it here, aren’t I?) A group of soldiers on training maneuvers in the Scottish highlands end up trapped in an isolated farmhouse, desperately trying to hold off the werewolves until dawn. What I found at once surprising — and ultimately unsettling — about this movie was the lack of movement on the part of the werewolves. I believe (don’t quote me on this; I could be wrong) that they were depicted by using people in costumes — people in unnatural postures, on stilts, perhaps; and given all that, the actors actually had very limited mobility. There’s almost no lunging or pouncing. What we have are instantaneous glimpses of nearly motionless werewolves — monsters frozen in terrifying silhouettes, looming in the shadows. And whether intentionally or not, this taps right into our childhood fantasies and nightmares. Think about it: as kids, the imagined images that scared us the most weren’t lunging enemies — they were the things that lurked . . . that watched us from the shadows . . . that towered over our beds. Capitalizing on that fear, Dog Soldiers delivers quite a bite!

to those two mighty pillars of the horror genre, the vampire and the werewolf. . . . Several friends had been recommending to me the film Dog Soldiers (2001). It is a genuinely creepy and entertaining story, and it’s the sort that I think I may like better on subsequent viewings. (To be 100% honest, after the way so many trusted friends raved about it, I was a tiny bit disappointed on my first watching; it’s a good film, but it had a lot of hype to live up to. But I liked it enough that I’m talking about it here, aren’t I?) A group of soldiers on training maneuvers in the Scottish highlands end up trapped in an isolated farmhouse, desperately trying to hold off the werewolves until dawn. What I found at once surprising — and ultimately unsettling — about this movie was the lack of movement on the part of the werewolves. I believe (don’t quote me on this; I could be wrong) that they were depicted by using people in costumes — people in unnatural postures, on stilts, perhaps; and given all that, the actors actually had very limited mobility. There’s almost no lunging or pouncing. What we have are instantaneous glimpses of nearly motionless werewolves — monsters frozen in terrifying silhouettes, looming in the shadows. And whether intentionally or not, this taps right into our childhood fantasies and nightmares. Think about it: as kids, the imagined images that scared us the most weren’t lunging enemies — they were the things that lurked . . . that watched us from the shadows . . . that towered over our beds. Capitalizing on that fear, Dog Soldiers delivers quite a bite!

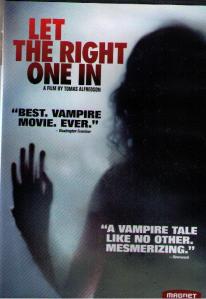

But far and away the best movie I saw this summer, irrespective of genre, was the vampire film Let the Right One In. It’s a Swedish film, so you have the option of watching it either in Swedish, with English subtitles, or dubbed into English. So far I’ve watched it once each way, and there are things I like better about each version. It’s dark, haunting, beautiful, sad, and it uses the canon of vampire mythos to help us ask some profound questions. Some critics call it a “fairy tale.” Perhaps. Again — without giving too much away — it’s the story of the bonding and love between two lonely children — one living, one a vampire. It’s skillful and subtle, and it’s so thought-provoking that some of us discussed it for weeks after I saw it.

But far and away the best movie I saw this summer, irrespective of genre, was the vampire film Let the Right One In. It’s a Swedish film, so you have the option of watching it either in Swedish, with English subtitles, or dubbed into English. So far I’ve watched it once each way, and there are things I like better about each version. It’s dark, haunting, beautiful, sad, and it uses the canon of vampire mythos to help us ask some profound questions. Some critics call it a “fairy tale.” Perhaps. Again — without giving too much away — it’s the story of the bonding and love between two lonely children — one living, one a vampire. It’s skillful and subtle, and it’s so thought-provoking that some of us discussed it for weeks after I saw it.

All right: that should give you puh-lenty of scary stories to chew on as we go into October (and it’s only the second day!). My plea for reader participation this week offers you two options. (Heh, heh — I hope this one fares better than my mythology quest, which went over like a lead balloon!) The first is obvious: tell us about great scary stories you’ve run into. What are your favorites? Under what circumstances did you experience them? How can we find them?

The second, if we can get a little creative, is this: we’re just now starting October. . . . If we act now, we can set up next week’s post. Use your imagination and come up with a sentence that suggests a spooky paragraph. Give us the first line. Evoke possibility. You don’t have to tell everything: the challenge is to suggest, to set questions exploding in the reader’s mind. Look back up to the very top of this post: that would be a perfect example. What makes that house different from all the others on the block? Surely you can think of one provocative sentence. If you devote some time to it, you’ll probably come up with five or ten set-up lines. You will probably have a hard time shutting yourself off. One of my own examples (which I’m probably misquoting) is the first sentence of my story “Shadowbender”: “Aunt Estelle wasn’t so bad; it was her house that bothered Shan.”

I’m inviting you to post a line — a sentence — that may yield a good, scary paragraph. Next week I hope to line up all these sentences and let readers choose one and try writing the paragraph it suggests.

As always, please remember that some younger people are reading the blog, too.

Meanwhile, happy October!