Today was one of those days when I just never quite got to writing. I had the Neo and the notes out, and I worked through some scenes in my mind; but I just didn’t write. I’ll chalk my foot-dragging up to one third laziness, one third caution [treading very carefully this close to the end of the story, not wanting to rush], and one third reluctance to finish — writing this book has been so pleasant that I’m sad to reach the end . . . but not really, and not for long — it’s good to get things finished. I’m estimating there are about three major scenes to go before the end. (Which probably means there will be five or six. Or ten?)

Concerning writing days, I’m a notoriously slow starter. I’ll do any number of things before I get around to writing: oversleep, dust some obscure shelf somewhere in my apartment, ride my bike to the store (the day never really begins for me until I’ve been outside), file some piece of paper that’s been waiting in some pending pile for too long, stare out the window, check e-mail, read some long-forgotten files in “my documents,” notice a book on my shelf that I really want to read soon, review my story notes, chew my fingernails, eat lunch, make coffee, take a long walk, open the refrigerator for no reason, lie down on the floor for awhile. . . . But once all the grains of sand build up to the point at which everything overbalances and the poles reverse [What kind of metaphor was that?! I don’t think that was legal, even with an artistic license.] — once that happens, then I’m scary. It’s like in the movie Troy, when Achilles gives Odysseus a good-sporting jibe for taking his sweet time in getting to Troy, and Odysseus says something like, “I don’t care whether or not I’m there for the beginning of the battle, as long as I’m there for the end!”

Be There For the End — See It Through — Go the Distance — those should be our goals as writers (or in doing whatever we do). Remember why the “Dead Poets Society” is called the “Dead Poets Society”? — It’s because the members are committed to living out their lives as poets. Poetry is a path that you must live to the end, and not turn aside. You’re finally really a poet-all-the-way when you’re a dead poet, when you’ve lived deeply and drunk life to the lees.

Anyway — I have to quote here from a comment that came into this blog last week, because it’s so well said that I wrote it out on a little piece of paper to keep in my “great quotes about writing” notebook. It’s from Catherine, who I’m quite sure will be writing professionally in the near future.

Last week, Catherine wrote:

“The settings and the music, especially, remind me of some idealized time in the past, when everything was wonderful except for what wasn’t; a time that I can only return to if I have a character whose life envelops me so completely that I can’t look out the window without seeing her through the trees.”

That describes so well the writing process when it’s working (for the kinds of stories, of course, that so many of us love)! If you get a character who’s absolutely real to you, and if you immerse your imagination in a setting that evokes that yearning for a remembered time that maybe you never actually lived through (because it’s been improved by your memory and the passage of years), then I think you’re well on your way to creating something extraordinary. Catherine, I’m in awe of how well you’ve summed this up! We’ve talked before about that C.S. Lewis concept of the longing we sometimes feel that does not have its fulfillment in anything we live through from the cradle to the grave — yet still we feel that yearning: and logically, when there is a yearning, there is the corresponding satisfaction of the yearning [there is food for our hunger, there is sleep for our tiredness, there is companionship for our loneliness, etc.] — and therefore, the longing that has no fulfillment in this life is a powerful indication of the existence of Heaven — of more to the picture than we presently see.

Hope Mirrlees explored that idea (indirectly) in Lud-in-the-Mist, and I think a lot of the other great stories do it, too.

A time in the past, when “everything was wonderful except for what wasn’t” — such is also true of the present, of the mundane — right now in our lives, everything is wonderful except for what isn’t. (When we’re older, these will be the times we look back to with our wistfulness and see all the magic that is here!) Yet a great deal of what is really true and what is beautiful seems to come into focus only when we’re well past it on our careening ride into the future. So, I think, so many of us writers look to our childhoods for the clarity and the perspective that makes a worthwhile story. Not that we always write directly about the things we did and thought then; but that we revisit something of what we felt and perceived in those distant days and shine a light on it through the filter of our experiences since then.

Here’s from Lud-in-the-Mist, by Hope Mirrlees:

“In [man’s] mouth is ever the bittersweet taste of life and death, unknown to the trees. Without respite he is dragged by the two wild horses, memory and hope; and he is tormented by a secret that he can never tell.”

Memory and hope, the two wild horses that drag and thrash man like a pair of Untowards — these, writers, are two of our most important tools. Bring them to bear!

When I was born, the road I lived on didn’t have a name — it just had a

Old Oak Road, looking north from in front of my yard

rural route number. Little by little, the city limits of Taylorville drew closer, and eventually the talk was flying fast and furious of naming the road. The default, front-running name was “Glen Haven Drive” — not because of any careful thought on anyone’s part, but because there is a Glen Haven Cemetery at the first bend in the road. My two childhood neighbor-friends and I intensely disliked that idea, because for one thing, who wants to live on a street named after a graveyard? For another thing, we didn’t like the sound of “Glen Haven” — it seemed ill-suited to a country road in central Illinois. So we thought about it for awhile and came up with “Old Oak Road,” because the road does have an abundance of old oak trees, particularly along its inhabited stretch, before it gives way mostly to fields farther north.

Following some advice from our parents about how to go about getting support for our idea, we boys took a petition up and down the road for the various homeowners to sign if they liked our name. (I don’t remember how old we were; I want to say I was about 9 or 10, which I think is pretty close.) Our dogs also came with us, as they did pretty much wherever we went on our bicycles or on foot; and when they encountered the homeowners’ dogs, they all went through the standard dog protocol of barking furiously at one another.

So our signature-gathering typically went like this:

“Hi! We’re BARK BARK BARK BARK to get BARK BARK BARK BARK BARK if you BARK BARK BARK BARK BARK.”

Sometimes the homeowners had questions, such as:

“What BARK BARK BARK BARK BARK BARK BARK?”

Old Oak Road, looking south from in front of my yard

Most often, they just signed the petition so we’d take our dogs and go. Then came a city council meeting at which the issue was debated (without dogs); and by, as I recall, a fairly narrow margin, we were awarded our tree-loving, heritage-rich name, and there were three happy little boys who got to live on a road that they’d named. I wish I had here in Japan the picture my mom took of us three kids with the road sign, but you’ll have to settle for the one I’ve got.

the corner of Lincoln Trail and Old Oak Road

Abraham Lincoln might conceivably have passed within sight of this oak in my front yard, since his law circuit would have taken him along this route between Allenton and Taylorville.

Anyway, that story is the background for telling you about a long poem my mom wrote shortly thereafter. Her poem was titled “Old Oak Road,” and it began with the creation of the world . . . yes, those six days when everything came ex nihilo by the spoken word of God. She traced the history of that region through the time of the undisturbed trees and the animals . . . to the long ages of the moccasined feet . . . to the coming of the white man . . . to the days when Abraham Lincoln rode along the dirt path there and saw the oak trees . . . to the era of the burgeoning community of Taylorville . . . and so at last to the time of the three boys with their bikes and dogs, who gave the road its name.

Yes, my two friends and I were the culmination of history! We all used to laugh together (Mom, too) about the grandiosity of the poem. It’s never been published except in a volume of my parents’ writings that I printed and bound as a surprise for them a long time later. But Mom did capture a certain intangible something there . . . some echoes of the fulfillment behind the yearning.

One quote from the poem that I’ve often used is this:

“Something whispered in their ears — something spoke from out of time . . . / From the places where they played. . . .”

Mom understood that the “places where we play” in our earliest years become for us a sacred well-spring, from which we draw water for various purposes all our lives. In most of what I do even now, the road and the oaks are whispering still.

And finally, one of the main places we played as kids was the barn behind my house. It’s described best in that same story, “Glory Day,” that I quoted from in the previous post. I promise not to do this every week, but let’s go there one last time. Again, there’s nothing fictional about this except the name “John.”

The barn had always called and whispered to John. If the fields and woods were sacred, then the barn was the chapel at the center of it all. It was entirely wooden, built eighty or ninety years ago. Though it no longer housed horses (Dad had sold Banner to a friend shortly after John was born), it was full of the memory of horses: ancient gray carpets of well-trampled manure and straw on the stall floors, the teeth-marks where horses had gnawed at the boards, and in one trough where mama cats sometimes had their kittens, there remained part of a salt-block for horses to lick — it shone in the dimness like a chunk of snow that never melted.

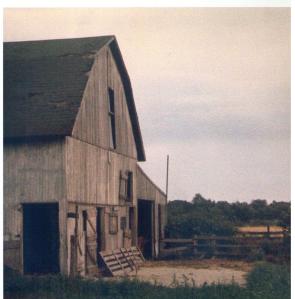

My barn: this photo was taken by my Cousin Steve either when I was a baby or before I was born; the barn as seen here is in slightly better shape than it was during most of our "glory days."

A central concrete walkway separated the lower floor into two rows of stalls. Those on the north were dark rooms with doors that closed, and where toadstools sprouted in the cool half-light. Virginia creeper thickly blanketed the entire north face of the barn outside, from the ground to the high hay-door. The vines’ roots sealed shut various hatches and trapdoors, and framed the windows that were open, so that what light entered was a green glow among fringes of bobbing leaves.

The south stalls were more open and airy, their walls mere rail fences that only rose chest-high. More of the outer wall on that side was missing, so that the sun had free access to bake the floor in shifting patches. Insects droned in and out; up under the rafters, mud daubers built nests resembling panpipes. Riots of foxtail and burdock, timothy and poison rhubarb spilled in through gaps near the foundation like crowds of clamoring fans desperate for glimpses of the inner world.

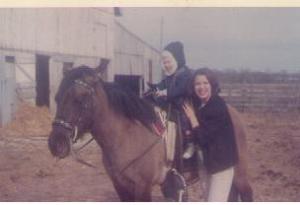

1968: That's me, with the barn in the background. That's a good friend of our family's, and I think that's her horse, not Dad's.

The wide main door on the west always stood open and could no longer be closed, its rollers rusted, its planks in the grip of maples that had grown up along the walls and become, with their counterparts on the north and east, a natural, supplemental framework, steadying the aged structure against the winds. At the barn’s east end, a ladder climbed to the hayloft.

The hayloft occupied the whole upper story, the roof arching high above its hay-littered floor like the keel of an overturned ship. Wooden beams transected the space in struts and arches. Birds nested in the eaves. The loft still saw active duty — the tenant farmer from up the road stored his hay bales there in stacked banks that rose to the upper braces. He would remove them a few at a time as needed, so that their cliffs changed as the seasons unfolded. But John and his friends considered the bales to be their own private set of giant building blocks. They could be positioned into tunnels and fortresses — hot, itchy, pitch-black crawlspaces delightfully scented of alfalfa and timothy. Bound at times into these hay-block walls were long, papery snake skins.

The loft was the perfect place for the long, aimless conversations of boyhood — the plans, the fancies, the arguments, the make-believe. And when no friends were available, it was the place to read. John sat in the open hatchway on the west, his feet dangling above the ground far below, and read Lovecraft and Dunsany and The Martian Chronicles.

And so the barn was. It was the best. Suggestion for comments: how about describing that place you played as a child, when summers went on forever, and you could read all day with impunity?

1968: Mom and me in the field. What, am I EATING the corn we're gleaning?!